B Cell Targeted Therapy

On March 28, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved a new drug called Ocrevus (ocrelizumab), the first and only treatment that fights both relapsing and primary progressive forms of multiple sclerosis (MS).

Ocrelizumab represents a shift in focus for MS drug design, as it is a first-in-class therapy that specifically targets CD20-positive B cells thought to be linked to myelin and axonal nerve damage. Until now, treatments and research had been targeting T cells alone, which is not as effective.

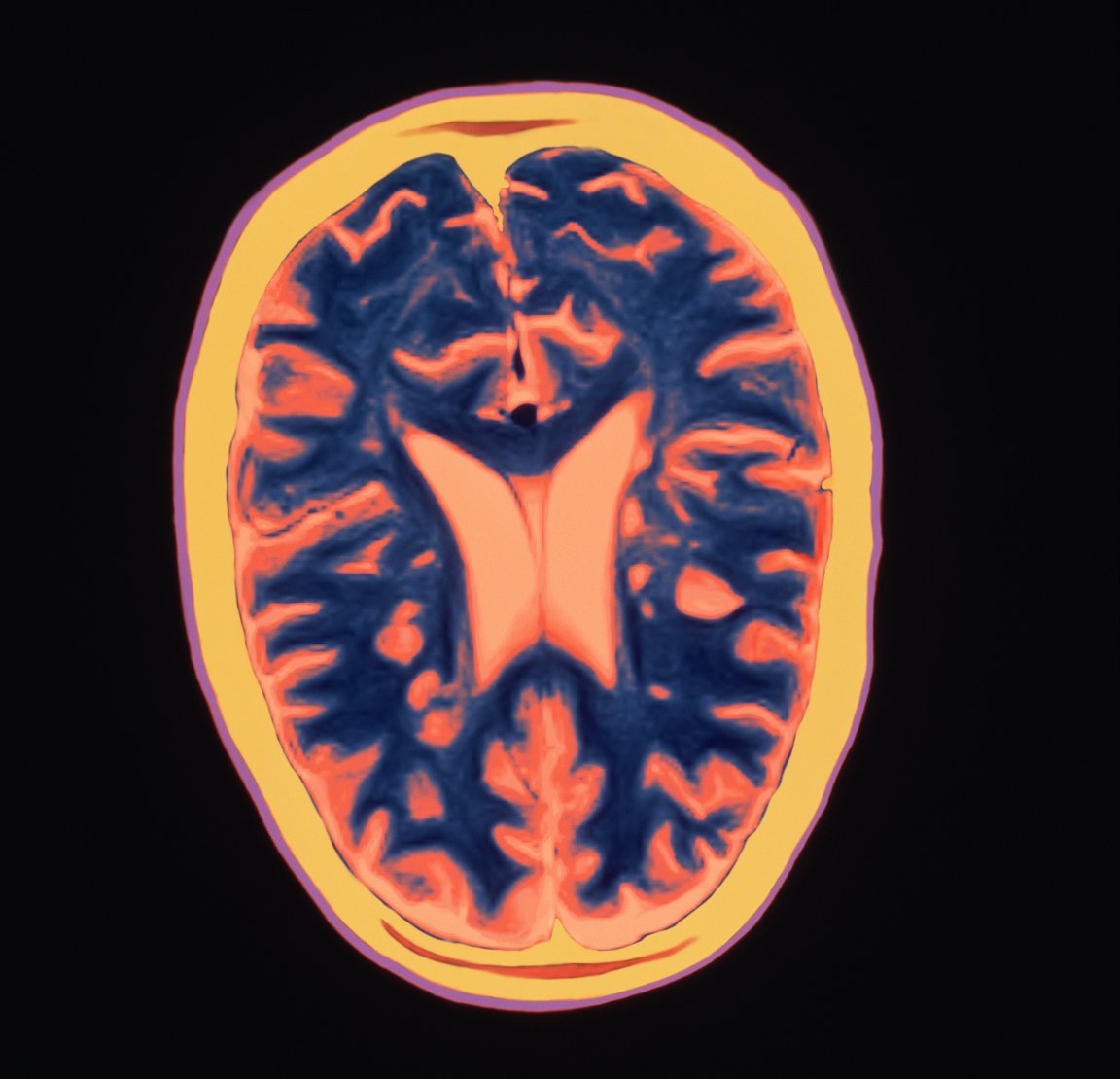

Approximately 400,000 people in the U.S. and more than 2 million worldwide suffer from MS, a chronic disease for which there is no cure. MS is characterized by abnormal attacks by the immune system on myelin sheaths of nerve cells in the brain, optic nerves, and spinal cord. The myelin sheath supports and insulates the nerve cells. When it is attacked, it becomes inflamed and eventually sustains damage. Symptoms of damage to the myelin sheath include fatigue, pain, muscle weakness, and difficulty seeing, which can eventually lead to disability, including the inability to walk.

MS is the leading cause of non-traumatic disability in younger adults, typically first striking between the ages of 20 and 40. Patients experience relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS), which is the initial diagnosis for 85 percent of MS sufferers, as episodes of new or worsening symptoms (relapses) with periods of recovery in between.

Most people with RRMS will eventually transition into a diagnosis of secondary progressive MS, which steadily worsens over time without periods of recovery just like primary progressive MS (PPMS) does. Everyone with any kind of MS experiences disease activity in the brain and nervous system even when they’re asymptomatic. For all of these reasons, reducing disease activity and slowing disease progression are critical components of treating MS.

Hope For The Future

Stephen Hauser of the University of California, San Francisco’s Weill Institute for Neurosciences, whose research led the drug’s development, told Scientific American that early use of ocrelizumab will allow patients with a new diagnosis of PPMS to “look forward to a full life without significant disability.” This treatment opens up a new option for people with RRMS, but even more significantly, represents the first disease-modifying therapy available for patients with PPMS.

Hauser and his team also see the fact that ocrelizumab provides primary progressive disease patients with only about a 25 percent benefit as useful from a research standpoint; it suggests that the progressive form of the disease is driven by a different biology. Since this research has proved that the B cell plays a key role in MS, but the majority of the immune cells found in MS lesions are T cells, the question is, what do B cells do within the disease process?

Hauser believes that the B cells may be “orchestrating” the T cell damage process, and notes that many other drugs used to treat MS interfere with B cells even as they target T cells. “Ocrelizumab’s success has led to a rethinking of how the other MS therapies may be working,” he remarked to Scientific American. “[O]ur foot is in the door, but we’re not there yet.”