The Next Big One?

Thomas Jordan, the director of the Southern California Earthquake Center, made some statements during his keynote address last night at the National Earthquake Conference that has raised some eyebrows…and more than a few heart rates.

“The springs on the San Andreas system have been wound very, very tight. And the southern San Andreas fault, in particular, looks like it’s locked, loaded and ready to go,” he said.

The last major temblor to strike the southern San Andreas fault system occurred in 1857—when the region was more untamed Wild West than glamorous (and heavily populated) Hollywood. That quake, the “Fort Tejon earthquake,” was a magnitude 7.9, comparable to the recent shakeup that struck Ecuador on April 16.

Ironically, the problem is that there have been so few major earthquakes in Southern California. This seems counterintuitive, but minor or mid-range quakes are a good thing, since they act to relieve tectonic stresses, and prevent them from accumulating in the first place.

But the San Andreas fault has not relieved these stresses for over a century; elsewhere, plate tensions have been gathering for much longer, upwards of 200-300 years.

Investing in New Tech

In 2008, the U.S. Geological Survey released some pretty frightening figures. They estimated that a magnitude 7.8 temblor along the southern San Andreas fault zone would occasion over 1,800 deaths, 50,000 injuries, and over $200 billion in long-term damages.

Jordan’s warning should come as a wake-up call for city planners, engineers, and public safety personnel in Southern California, and is a powerful reminder—particularly in light of the many major earthquakes that have struck heavily populated areas since the beginning of the 21st Century—of the importance of investing in earthquake detection and earthquake-proofing technology.

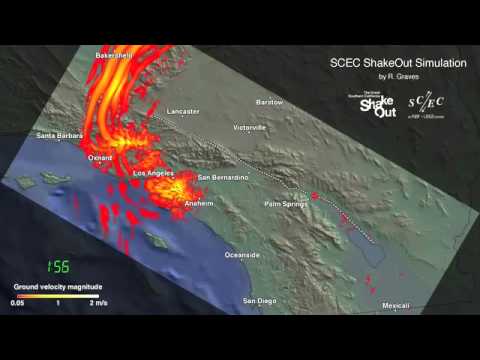

Supercomputer technology, for instance, has enabled researchers to simulate the catastrophic effects of these “big shakes” on the cities and populous regions of the threatened area. Such a supercomputer simulation, run at the Southern California Earthquake Center in 2010, showed the unexpected effects of a magnitude 8 quake on the L.A. Basin—a consequence of liquefaction of the soft soils in the basin.

And more recent simulations cited by Jordan indicate that although Los Angeles is 30 miles away from the San Andreas fault, the San Gabriel mountains would likely reflect seismic waves back toward the city, increasing the danger.

The San Andreas fault is probably already the most heavily studied and monitored earthquake-prone area in the world, but further investment in early warning seismometers and detection technology may just give threatened populations the edge they need to survive the next major catastrophe.

And shoring up weaknesses in building materials, construction methods, telecommunication systems, and aqueducts would significantly lessen the impact and shorten the post-disaster recovery time.