Bone and cartilage regeneration has moved a step closer to reality. Scientists have successfully formed “bone-like structures” in mice using a new stem cell-based technique, which they believe could be transferred to humans.

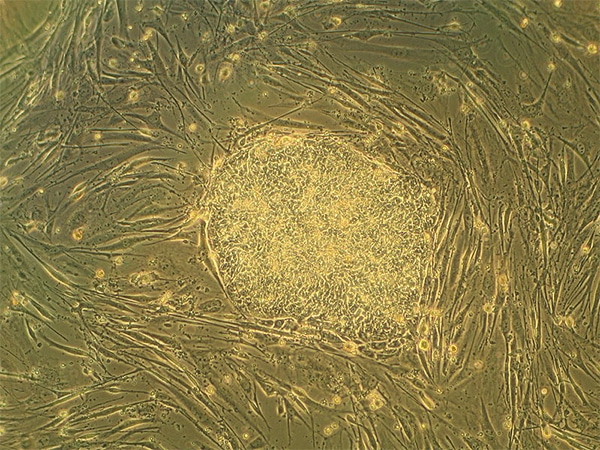

Developed by scientists at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston (UTHealth), Monash University and RIKEN Centre for Developmental Biology, the technique allowed the creation of cells that have the appearance and behaviour of normal cells in the stage just before they form cartilage.

When the researchers transplanted these special proto-cartilage cells – more accurately known as chondrocyte precursor cells – into mice, they developed into structures that had the appearance and characteristic of bone.

According to the researchers, the technique can be easily scaled up to generate large numbers of these cells at once, giving it serious potential for human use.

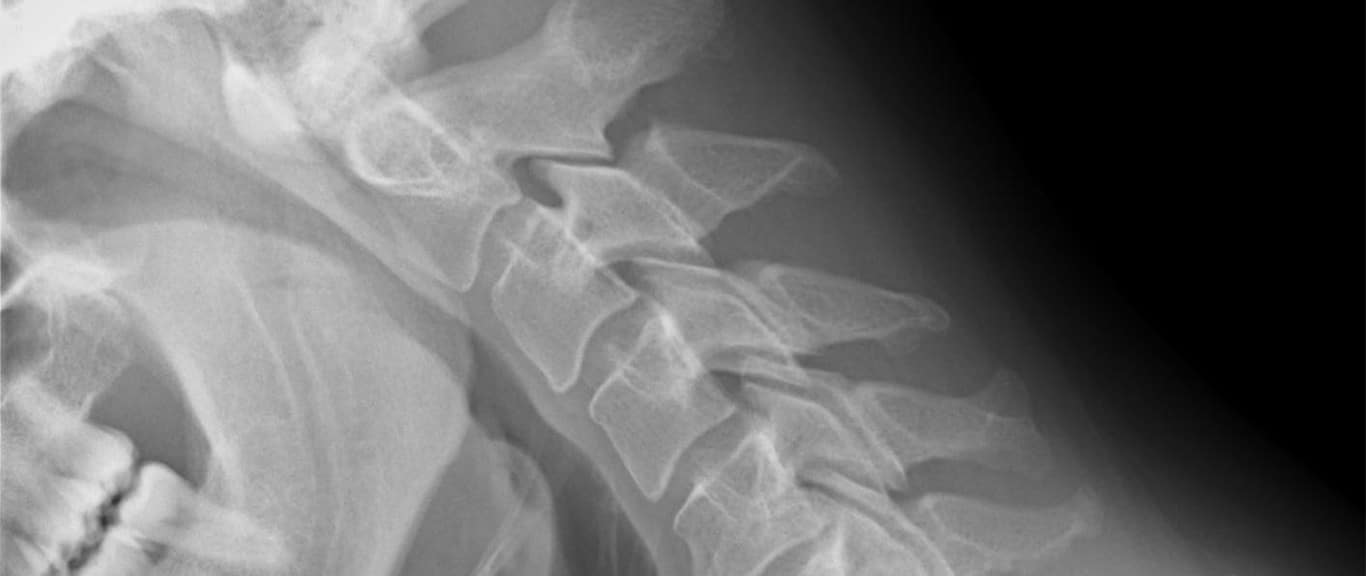

The research has particular potential for the repair of damaged cartilage and bone in joints and the spine – conditions that plague professional athletes and those who do a lot of manual labour as part of their jobs.

For those who don’t know, stem cells are cells in the body that are not specialised for any particular function and which can in some circumstances be made to turn into other cells. They have previously been researched for bone regeneration, but with only limited success.

The reason for this is that previous research has used adult stem cells, which are located in the area trying to be regenerated and already have some of the properties of normal cells in that part of the body.

This new research, however, has focused on the use of embryonic stem cells, which are extracted from an embryo (in this case of a mouse) and so have the potential to become a far wider range of cells than their adult counterparts.

However, to make any form of stem cells become a specific cell type, scientists need to use a second component to trigger a change in the cell.

“Current cell generation strategies generally use proteins to direct the stem cells to give rise to functional cells of interest,” explained Dr Naoki Nakayama, holder of the Jerold B Katz Distinguished Professorship in Stem Cell Research at the UTHealth Medical School.

However Nakayama believes that proteins aren’t the best tool for the job, as they use a lot of different mechanisms to make changes to the stem cell, and not all of them help to create the desired final cell. They are also very expensive, making them far from ideal for the task.

Instead this research used tiny organic compounds known as small molecules for the task, which are growing in popularity for use in stem cells.

“Small molecules are generally longer-lasting than proteins in culture and also inexpensive to produce to a large scale. They can also allow a particular mechanism to be more precisely activated,” said Nakayama.

The research was published today in the stem cell research journal Development.