Power to the Patient

Medicine is coming to your living room. In fact, you could argue that it’s already there. The first at-home pregnancy kit hit the U.S. market in 1976 (then it was called E.P.T. — first for “early pregnancy test” then for “error-proof test,” which, of course, it was not). Since then, it’s gone through a number of iterations — color-changing test strips, plus or minus signs — leading up to the tests on the market today, many of which have digital readouts that simply say either “pregnant” or “not pregnant.” Now, the technology is so cheap and ubiquitous that furniture company Ikea used it in a recent advertisement, offering crib discounts to pregnant women whose hormone-laden urine revealed a special discount code.

The vision of the at-home pregnancy test was a noble one: A woman could walk into her local pharmacy and purchase some medical-grade clarity about her reproductive future, without the immediate need to discuss sensitive or taboo subjects with doctors.

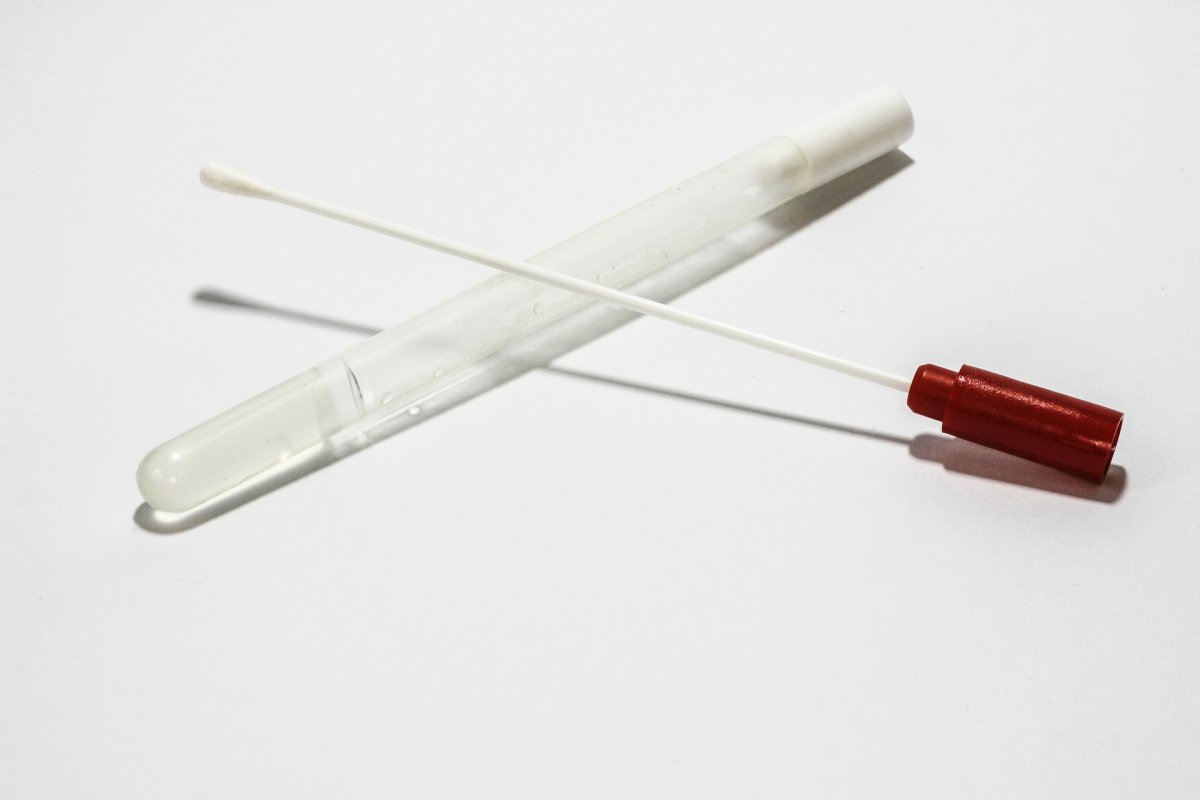

Today, at-home assessments can test for much more than pregnancy. You can pick up tests for urinary tract infections, assess fertility by way of ovarian egg reserve, and check for sexually transmitted diseases at your local pharmacy. Even genetic testing kits like 23andMe are now available at retailers like Walmart. The internet holds other types of kits to help consumers discover everything from their ancestry to their complete microbiome.

These tests are part of a larger healthcare trend toward improving patient access to medical services while reducing their cost. The market for DIY medical tests is rapidly growing: It’s projected to reach $340 million by 2022 as existing tests become more affordable and scientists develop completely new tests.

On an economic level, direct-to-consumer (DTC) medical tests could help low income or rural families access affordable medical care, no matter whether they’re insured, and reduce healthcare costs overall.

Already, when a consumer considers taking a DIY test, the question is often not can they test for a specific condition, health trait, or genetic predisposition — but should they? For now, the answer may be fairly straightforward. But as the tests evolve to encompass a broader scope of conditions, that may no longer be the case.

DI-Why?

There’s not just one reason why patient-consumers are drawn to at-home medical tests. Health problems — either for the individual or for someone in the immediate family — may prompt people to want to learn more about what’s going on in their bodies. But the affordability, accessibility, and usability of at-home medical tests have allowed many people to partake purely out of curiosity.

For many consumers, at-home medical tests are appealing not just because they’re convenient and discreet compared to traditional medical care, but they can be more affordable. Let’s take, for example, a person with a sore throat and a fever. This person has no health insurance or primary care doctor. They also don’t live close to community health or urgent care clinics, where patients can often be seen more quickly (and for less money) than a primary care doctor. While it may seem unfathomable to people living in urban areas, it’s not unusual in more rural parts of the U.S. for people to travel great distances to access healthcare. As a result, it’s not uncommon for patients to resort to going to the emergency room to get a strep test, particularly if they are also uninsured.

Our example patient with a sore throat may do this, and if the test is positive, the ER doctor would be able to write them a prescription for antibiotics. The cost of that visit without insurance doesn’t just factor in the test and the medication — the patient is also then paying the fee for the physician and the hospital. Depending on where the patient lives, the cost for the entire visit could rack up bills totaling in the hundreds or thousands.

But a rapid strep test kit purchased at her local CVS (or even on on Amazon) only costs around $35. If the test is positive, the patient’s doctor may be willing to call in a prescription for the antibiotics needed to treat it, which typically cost around $5 at most major retail pharmacies. At-home medical tests that are used to diagnose a condition like strep could cost even less for patients who do have insurance; while patients would still have to pay up front, as Consumer Reports noted in 2015, several major insurance companies reimburse the cost of the test if it’s ordered by a patient’s doctor and deemed to be medically necessary.

For now though, insurance companies don’t cover some kinds of kits, like those for genetic tests, because they aren’t diagnostic. But often, consumers don’t care. Many patients have spent years searching for answers about their health, their ancestry, or what they may pass on to a child. And for them, you can’t put a price on the information genetic testing can provide.

Hatie Parmeter, a 26-year-old from Chicago, tried 23andMe in hopes that it might provide some insight into a number of chronic health problems she’s suffered throughout her life.

“I’ve had many, many blood tests done for all sorts of things, but I didn’t have health insurance at the time and couldn’t do further medical testing,” she told Futurism. While the test didn’t reveal much actionable information related to her health troubles, Parmeter did find her ancestry results intriguing and didn’t regret the purchase. And just because her results were more entertaining than useful doesn’t mean others might not find the tests life-changing, Parmeter added.

Other consumers are heartened that their data could improve medical science, making life better for themselves or others down the line. While patients are the intended market, scientists are also interested in DTC medical tests and are eager to use the data collected by companies that sell the tests. That’s especially true for researchers working in fields that need a lot of data, such as genetics and the microbiome.

“Not everyone is as excited for people to use their genetic data for anything as I am, but this really intrigued me — especially as a rare disease patient,” said Kirsten Schultz, 29, a sex educator in Wisconsin. Schultz, who has a rare autoimmune disorder called Still’s Disease and uses the pronoun “they,” originally set out to take the genetic test offered by 23andMe in hopes of understanding more about their ancestry and genetic background, as their father didn’t know much about his family line. Aside from what Schultz obtained about their own genetics, they also liked knowing that they had donated their genetic intel to broader research efforts. “That might help find new correlations and help…other patients, too,” they said.

Once these patients have figured out why they might want to take an at-home medical test, there are other questions to answer. Is the test’s upfront cost reasonable? Are the results comprehensible and actionable? How likely are false positives or false negatives?

Those last two questions aren’t left up to the individual — that’s where scientists and regulators come in.

The Doctor Is At Home

Yes, DTC medical tests can be interesting. Sometimes they’re even useful.

But most healthcare professionals and scientists know that the tests available over-the-counter are not quite the same (often less precise) as the ones a physician might order. Patients are often less comfortable collecting some of the biological samples that doctors might require, like blood (with the exception of diabetes patients who monitor their glucose levels at home, most patients are not yet taking their own blood samples), vaginal secretions, or a stool sample, though some tests do require users to submit those.

The simplest at-home tests detect a single biomarker in the body: it’s either there or it’s not. That’s how pregnancy tests work — a urine sample is tested for the assay human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), a hormone the body begins to produce once an embryo has attached to the uterine wall. If someone participated in a risky activity with someone who might be HIV-positive, a blood test can determine if they, too, are infected with the virus. Having that information can help patients figure out the next step in treatment or medical care.

But most human health conditions aren’t quite so straightforward. Take, for example, genetic testing for the BRCA gene (linked to risk of breast cancer). This test, like other genetic tests, relies on assays, an evaluation of a biological sample that measures the amount of a particular substance, not simply its presence or absence. For patients who are showing symptoms of diabetes, testing their blood glucose levels throughout the day can help them manage the disease over the long-term. Tests for other substances like cholesterol, which can contribute to cardiovascular disease, might signal to a person to make lifestyle changes to lower their risk.

Most data is not useful until it’s interpreted, and genetic data is no different. While many tests on the market that are available to consumers offer interpretation as part of the results, it may not be as in-depth as the discussion a person might have with their doctor. A corporation that processes a huge volume of samples can’t interpret an individual’s results with as much nuance as a doctor who has access to a patient’s health history and family history would.

Getting to “Joe Schmoe”

Every test comes with some risk — the risk that patients could misinterpret their results and make health decisions based on them that are unnecessary, costly, or even dangerous; the risk that the tests themselves may produce incorrect results. In the latter case, a patient may respond to a false positive or fail to take action in the face of a false negative.

To limit those risks, DTC medical tests need both regulators and research to reach patients.

Because the FDA considers at-home tests to be devices, the time from lab bench to a patient’s hands is much shorter than it would be for a drug. “Devices are not like drugs…device development is a lot faster,” Courtney H. Lias, the director of the FDA’s Office of In Vitro Diagnostics and Radiological Health, responsible for regulating both in-home and lab-based diagnostic tests, explained to Futurism. For the FDA to approve a DTC test, a consumer needs to be able to get an accurate result, interpret the test in the way it’s supposed to be interpreted, and ultimately have the test’s benefits outweigh its risks, Lias said.

Throughout the FDA’s approval process, the agency is looking for data and supportive evidence of not only the test’s efficacy, but also its usability. “If ‘Joe Schmoe’ goes into the drugstore and buys this, how will it work in his hands?” Lias said. End-user testing for new kits is key; if the kit is going to be marketed to average people, then the company hoping to get the kit approved needs to demonstrate that prospective users can actually use it as intended.

If ‘Joe Schmoe’ goes into the drugstore and buys this, how will it work in his hands?

But more importantly, the test results have to be easy to decode. Can Joe Schmoe interpret the results of the test he bought at CVS? What happens if the test strip turns red for a positive result but Joe is colorblind? Does he understand that a “negative” result isn’t necessarily “bad” — or that a positive result isn’t always “good?” Does he know when to call his doctor?

Many companies creating at-home medical tests are giving consumers more than just the test itself — they also offer services that help consumers navigate and interpret their results, such as portals or graphics that show their risk relative to others who have used the service, and may even connect them with genetic counselors or other resources. Regulating this component is where the stakes are high for both consumers and companies. Whose fault is it if a patient misinterprets the test? If a patient gets a false positive test for HIV, who is accountable for how that mistake may well have completely upended that patient’s life and potentially required them to undergo arduous medical treatment and emotional anguish that was ultimately unnecessary? Who pays that patient damages?

In the past, the FDA has signaled that it might crack down on at-home medical tests — in 2013, the agency restricted the kinds of tests 23andMe could offer. But more recently, it seems to be taking a looser tack. In November 2017, the FDA released a statement indicating that the agency is creating a less-burdensome framework so that it can quickly approve medical advances, including tests, that it deems “truly novel.”

Some physicians whose patients use DTC tests don’t think we’re at the point of discussing regulation — they still question whether DTC has any clinical value at all. In fact, some medical professionals have found that DTC testing drives up costs, burdens providers, and are ultimately of “low-value,” if not no value, to patients.

As the tests get more sophisticated and varied, regulators, researchers, and physicians will continue to determine the kind of balance they want to strike between granting patients access to the tests they want and making sure those tests are safe.

The Future of At-Home Medicine

As technology progresses, new tests, along with other forms of DTC medical care, will fill in gaps in the existing medical system. Not only can doctors video chat with one another to review case notes, but patients can engage with their physicians — even having consults or exams — via Skype and with the help of wearables that can transmit their vitals directly into a portal for their doctor to review.

As the technology that makes such remote encounters possible becomes more refined, doctors may one day be able to make “digital house calls” when patients are ill or injured. That would improve the efficiency and affordability of medical care, providing a boon to public health: If a physician can remotely determine if a patient has an infectious disease, the patient wouldn’t have to come to a public medical facility and risk infecting others. Ultimately, it could reduce the spread of those kinds of illnesses.

As more citizens seek to keep medicine at home, and clinicians integrate DTC tests into patient care, the types of tests we might have in the future are only limited by what scientists can devise, and what the public demands.

But even if the tests work perfectly — the consumer uses the test correctly, the results are accurate — the information can quickly take patients to a dark place. Test results can portend a grim future, immediate or delayed, probable or definite. Patients and their families who might have just been doing the test out of curiosity have to be ready to accept that, or take steps to prevent it.

One thing is clear: Tests are about to get a whole lot more sophisticated. Today, people trying to get pregnant can take an at-home test to determine their most fertile window every month. But what if a test could tell them that an egg carried a number of genetic defects, an early indicator that a miscarriage could be more likely, or that a fetus could develop abnormally?

Perhaps, to us, that seems like science fiction, the next technology featured on Black Mirror or its ilk. We might not be able to predict in what directions the burgeoning industry of at-home medical tests will expand, but we can be assured that it will. Patients, physicians, and regulators may all have to rethink what roles they play, but chances are these changes will be for the better; after all, a century ago, the idea of peeing on a stick to find out if you would have a baby would have seemed nothing short of miraculous.