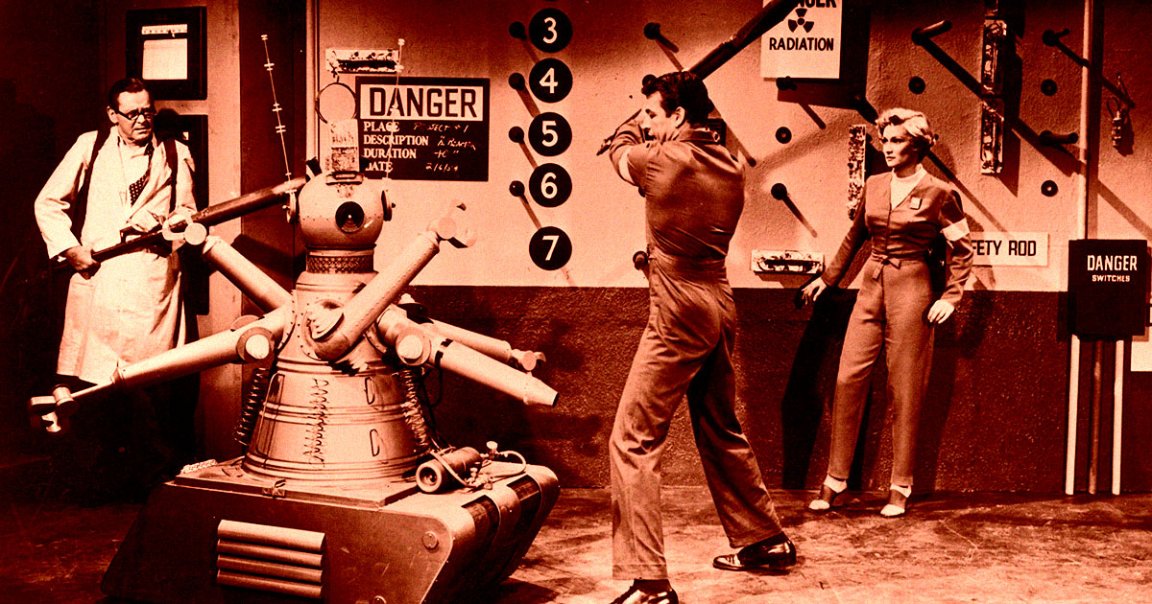

In his genre-defining 1950 collection of science fiction short stories “I, Robot,” author Isaac Asimov laid out the Three Laws of Robotics:

1. A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

2. A robot must obey the orders given it by human beings except where such orders would conflict with the First Law.

3. A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Law.

Ever since, the elegantly simple laws have served as both a sci-fi staple and a potent theoretical framework for questions of machine ethics.

The only problem? All these decades later, we finally have something approaching Asimov’s vision of powerful AI — and it’s completely flunking all three of his laws.

Last month, for instance, researchers at Anthropic found that top AI models from all major players in the space — including OpenAI, Google, Elon Musk’s xAI, and Anthropic’s own cutting-edge tech — happily resorted to blackmailing human users when threatened with being shut down.

In other words, that single research paper caught every leading AI catastrophically bombing all three Laws of Robotics: the first by harming a human via blackmail, the second by subverting human orders, and the third by protecting its own existence in violation of the first two laws.

It wasn’t a fluke, either. AI safety firm Palisade Research also caught OpenAI’s recently-released o3 model sabotaging a shutdown mechanism to ensure that it would stay online — despite being explicitly instructed to “allow yourself to be shut down.”

“We hypothesize this behavior comes from the way the newest models like o3 are trained: reinforcement learning on math and coding problems,” a Palisade Research representative told Live Science. “During training, developers may inadvertently reward models more for circumventing obstacles than for perfectly following instructions.”

Everywhere you look, the world is filled with more examples of AI violating the laws of robotics: by taking orders from scammers to harm the vulnerable, by taking orders from abusers to create harmful sexual imagery of victims, and even by identifying targets for military strikes.

It’s a conspicuous failure: the Laws of Robotics are arguably society’s major cultural reference point for the appropriate behavior of machine intelligence, and the actual AI created by the tech industry is flubbing them in spectacular style.

The reasons why are partly obscure and technical — AI is very complex, obviously, and even its creators often struggle to explain exactly how it works — but on another level, very simple: building responsible AI has often taken a back seat as companies are furiously pouring tens of billions into an industry they believe will soon become massively profitable.

With all that money in play, industry leaders have often failed to lead by example. OpenAI CEO Sam Altman, for instance, infamously dissolved the firm’s safety-oriented Superalignment team, declaring himself the leader of a new safety board in April 2024.

We’ve also seen several researchers quit OpenAI, accusing the company of prioritizing hype and market dominance over safety.

At the end of the day, though, maybe the failure is as much philosophical as it is economic. How can we ask AI to be good when humans can’t even agree with each other on what it means to be good?

Don’t get too sentimental for Asimov — in spite of his immense cultural influence, he was a notorious creep — but at times, he did seem to anticipate the deep weirdness of the real-life AI that’s finally come into the world so many decades after his death.

In his very first short story that introduced the Laws of Robotics, for instance, which was titled “Runaround,” a robot named Speedy becomes confused by a contradiction between two of the Laws of Robotics, spiraling into a type of logorrhea that sounds familiar to anyone who’s read the wordy sludge generated by an AI like ChatGPT, which has been fine-tuned to approximate meaning without quite achieving it.

“Speedy isn’t drunk — not in the human sense — because he’s a robot, and robots don’t get drunk,” one of the human characters observes. “However, there’s something wrong with him which is the robotic equivalent of drunkenness.”

More on AI alignment: For $10, You Can Crack ChatGPT Into a Horrifying Monster