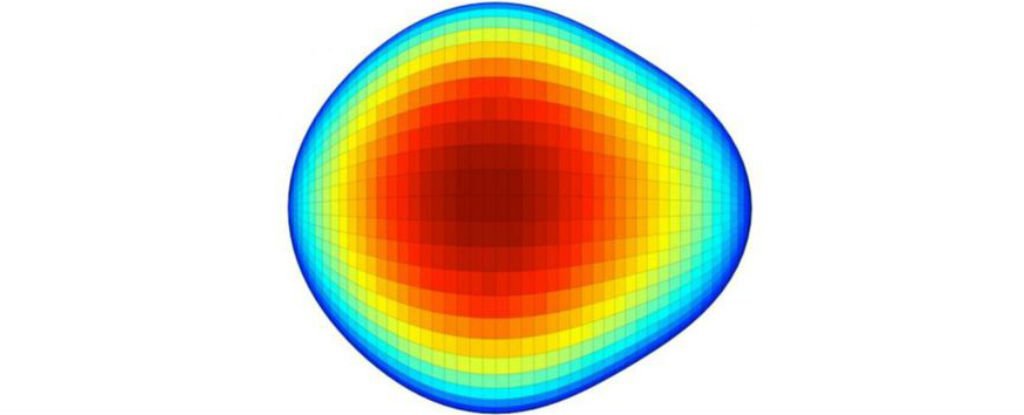

Pear-shaped

A new form of atomic nuclei has been confirmed by scientists in a recent study published in the journal Physical Review Letters. The pear-shaped, asymmetrical nuclei, first observed in 2013 by researchers from CERN in the isotope Radium-224, is also present in the isotope Barium-144.

This is a monumental importance because most fundamental theories in physics are based on symmetry. This recent confirmation shows that it is possible to have a nuclei that has more mass on one side than the other. “This violates the theory of mirror symmetry and relates to the violation shown in the distribution of matter and antimatter in our Universe,” said Marcus Scheck of University of the West of Scotland, one of the authors of the study.

Until recently, there were three shapes of nuclei — spherical, discus, and rugby ball. There is a specific combination of protons and neutrons in a certain type of atom that dictates the shape formed by the distribution of charges within a nuclei. These three shapes are all symmetric and agree with the theory known as the CP-symmetry, the combination of charge and parity symmetry.

In the end, this could help us understand why our universe is the way that it is. As astrophysicist Brian Koberlein notes, “It’s been proposed that a violation of CP symmetry could have produced more matter than antimatter, but the currently known violations are not sufficient to produce the amount of matter we see. If there are other avenues of CP violation hidden within pear-shaped nuclei, they could explain this mystery after all.”

No time travel?

This uneven distribution of mass and charge in the nuclei causes the isotope to ‘point’ in a certain direction in spacetime, and the team suggests that this could explain why time seems to to only go forward and not backward.

“We’ve found these nuclei literally point towards a direction in space. This relates to a direction in time, proving there’s a well-defined direction in time and we will always travel from past to present,” Marcus Scheck from the University of the West of Scotland told Kenneth MacDonald at BBC News.

That said, it is a rather speculative hypothesis, but it does raise some rather interesting avenues for investigation.

In the end, this recent discovery is another indication that the Universe might not be what we thought, which could propel us to a new era of theoretical physics.