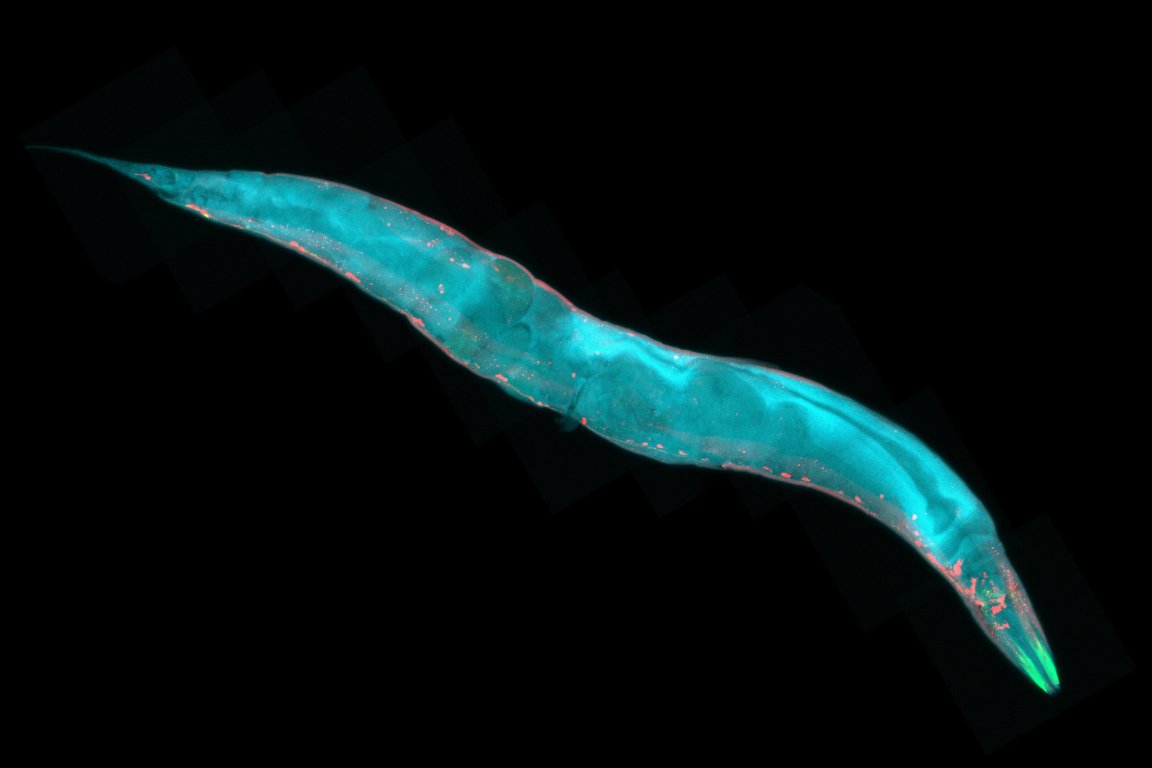

Researchers at the Baylor College of Medicine have found the key to longevity in Caenorhabditis elegans (C. elegans) worms — and maybe, someday, humans. The team noticed that genetically identical worms would occasionally live for much longer, and looked to their gut bacteria to find the answer. They discovered that a strain of E. coli with a single gene deletion might be the reason that its hosts’ lives were being significantly extended.

This study is one among a number of projects that focus on the influence of the microbiome — the community of microbes which share the body of the host organism — on longevity. Ultimately, the goal of this kind of research is to develop probiotics that could extend human life. “I’ve always studied the molecular genetics of aging,” Meng Wang, one of the researchers who conducted the study, told The Atlantic. “But before, we always looked at the host. This is my first attempt to understand the bacteria’s side.”

Even in cases like this, where it seems fairly obvious that the microbiome is influencing longevity, parsing out the details of how and why this happens among a tremendous variety of chemicals and microbe species is extremely complex. The team, in this case, was successful because they simplified the question and focused on a single relationship.

Practical Applications

Genetically engineering bacteria to support and improve human health and even to slow aging — and turning it into a usable, life-extending probiotic — won’t be easy. It is extremely difficult to make bacteria colonize the gut in a stable manner, which is a primary challenge in this field. The team, in this case, is looking to the microbiome, because the organisms used would be relatively safe to use because they would originate in the gut.

Clearly, researchers don’t know yet whether these discoveries will be able to be applied to people, though it seems promising. Despite the obvious differences between the tiny C. elegans worm and us, its biology is surprisingly similar; many treatments that work well in mice and primates also work in the worm. The team will begin experiments along these same lines with mice soon.

Other interesting and recent research hoping to stop or slow the march of time includes work with induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells, antioxidants that target the mitochondria, and even somewhat strange work with cord blood. It seems very likely that we won’t have a single solution offering immortality anytime soon, but instead a range of “treatment” options that help to incrementally hold back time. And, with an improving quality of life, this kind of life extension sounds promising.