Identity Congruence

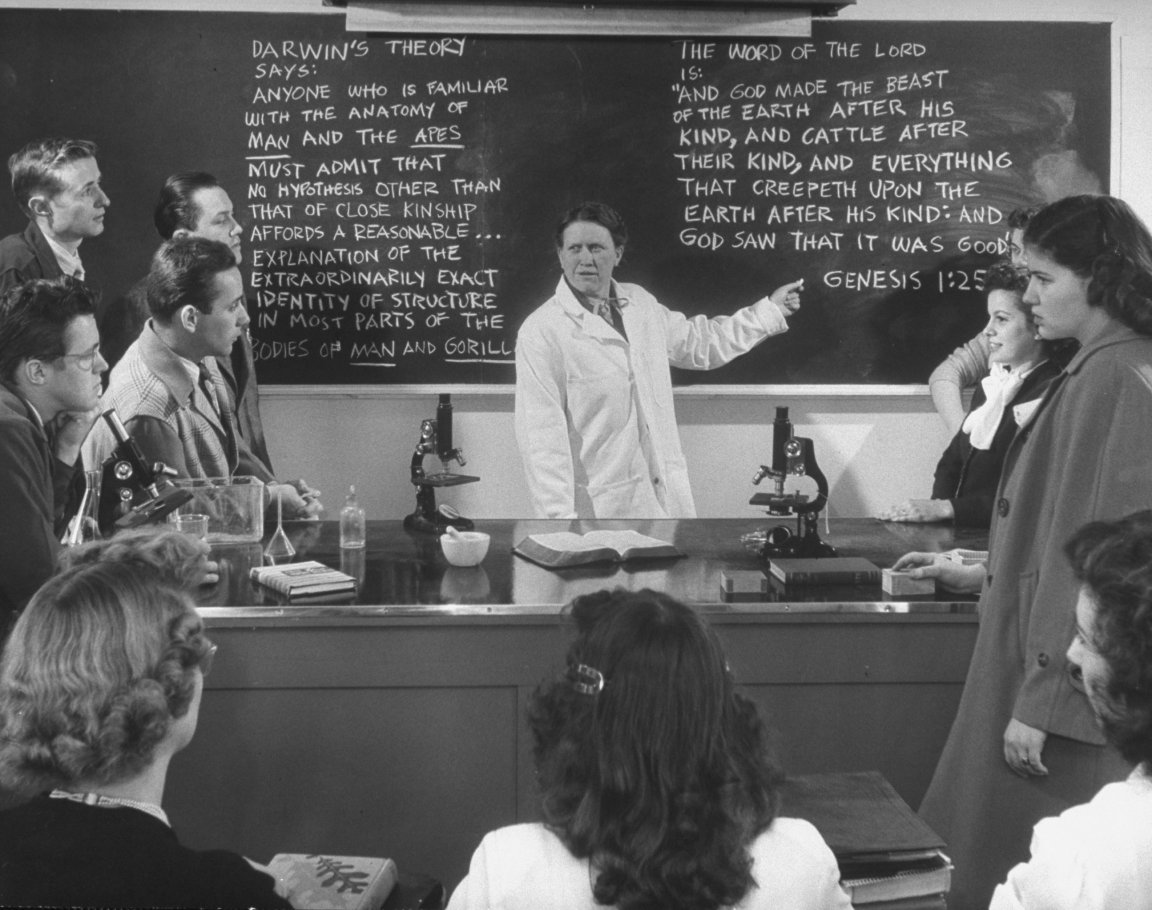

People tend to stick to the facts — usually. That’s certainly true of those in the science community, where facts rule the day, especially when backed by substantial evidence and data. For most people, this works out just fine. For some, it doesn’t. This seeming resistance to scientific messages has caught the attention of psychology researchers, and they’ve worked out a theory that could explain how people who hold science-skeptical views think.

The researchers used surveys, experiments, observational studies, and meta-analyses to arrive at some very interesting conclusions about how smart people can become science skeptics. It turns out, it’s not ignorance — these people have access to the same information and data as everyone else. According to an interview in Phys.org with researcher Matthew Hornsey from the University of Queensland, people just tend to choose which pieces of information to take note of “in order to reach conclusions that they want to be true.”

Dan Kahan from Yale University explained that “the deposition is to construe evidence in identity-congruent rather than truth-congruent ways, a state of disorientation that is pretty symmetric across the political spectrum.” Troy Campbell from the University of Oregon described the phenomenon succinctly, saying, “People treat facts as relevant more when the facts tend to support their opinions. When the facts are against their opinions, they don’t necessarily deny the facts, but they say the facts are less relevant.”

Effective Science Communication

It would seem that the difficulty isn’t in the facts per se, but in how people choose to see them. The researchers, who presented their respective findings at the Society for Personality and Social Psychology’s (SPSP) Annual Convention on January 21, think that it will take more than just “evidence” or “data” to change a skeptic’s mind about something.

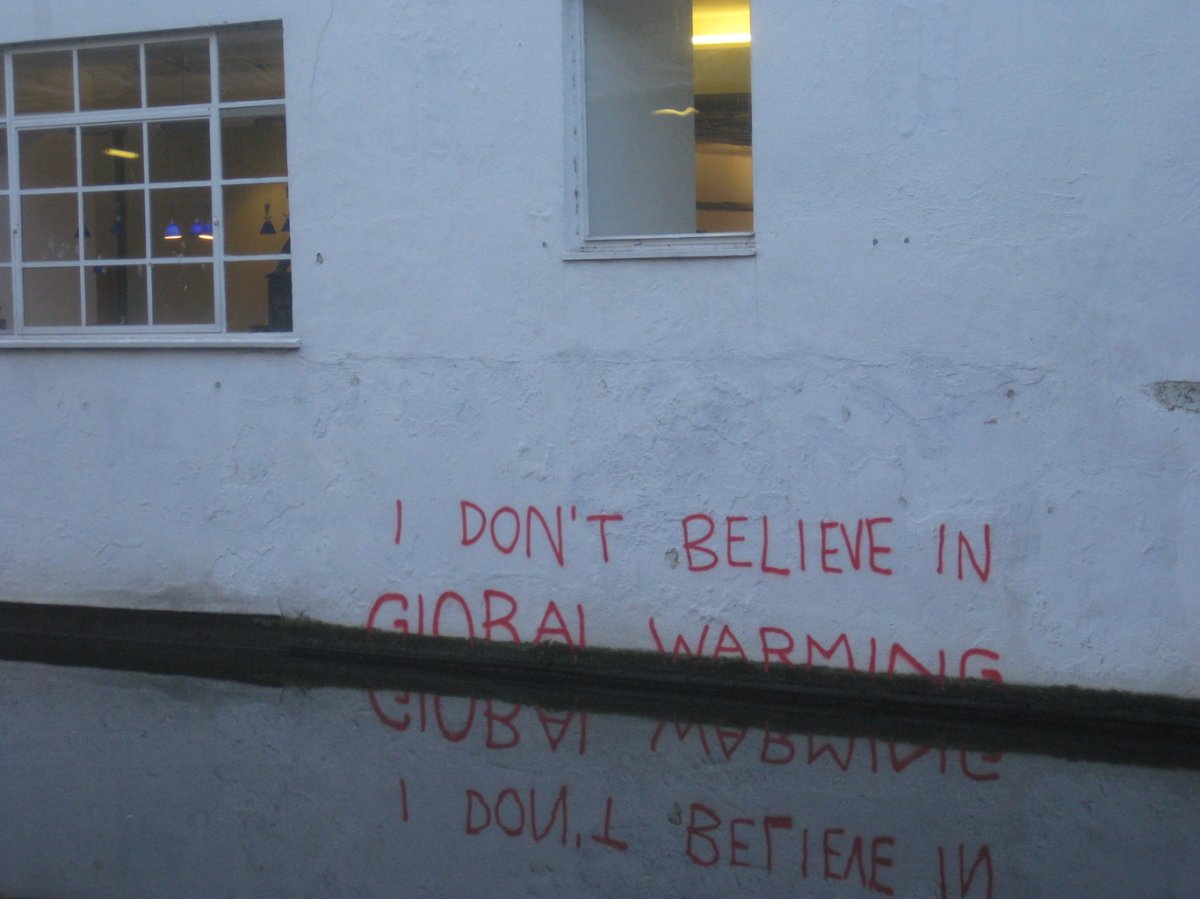

Many relevant scientific issues that are at the forefront of the societal conversation today, such as climate change, genetically modified organisms, or the safety of vaccines, are currently facing a healthy number of skeptics. The thing is, even skeptics and science deniers use science to defend their positions. “Where there is conflict over societal risks — from climate change to nuclear-power safety to impacts of gun control laws, both sides invoke the mantel of science,” says Kahan.

The researchers propose an alternative way of communicating to skeptics. They suggest identifying their underlying motivations or what Hornsey calls “attitude roots.” “Rather than taking on people’s surface attitudes directly, tailor the message so that it aligns with their motivation. So with climate skeptics, for example, you find out what they can agree on and then frame climate messages to align with these,” he explains.

In short, the key is better communication and using scientific data smartly, not just bombarding people with facts. Science has to learn how to talk to people more authentically and not just put the numbers out there if we want to do a better job of getting everyone on the same page.