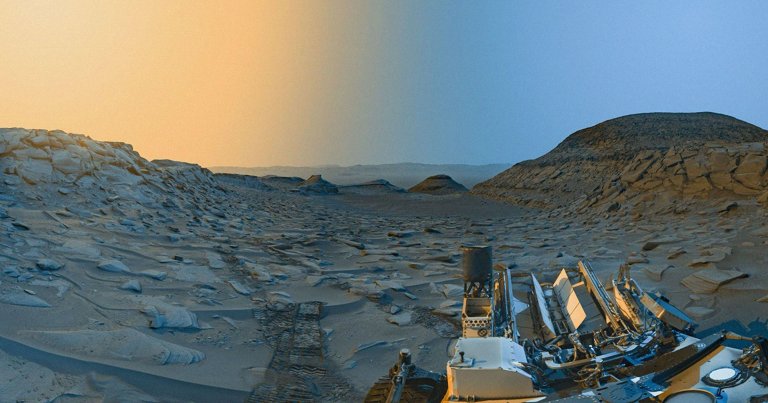

Space

Advancements in spaceflight are accelerating humanity faster and farther than ever before. From commercial companies like SpaceX offering vacations in space to NASA innovations that are forging us into a multiplanetary species, we’ll look at the latest space missions and milestones that are leading us into the final frontier.