Good Worming

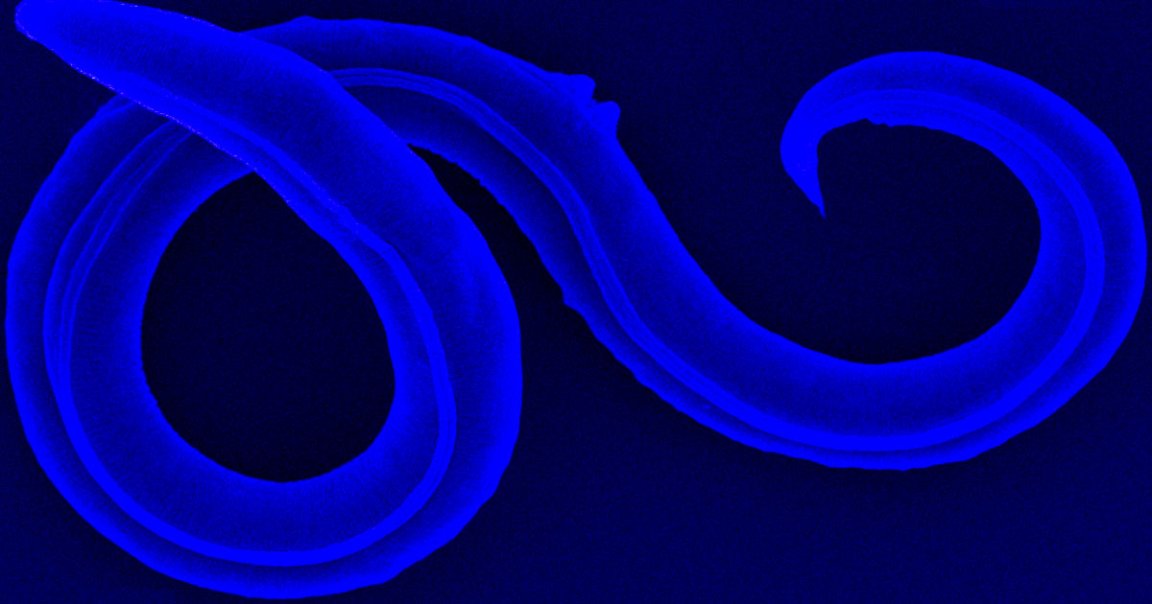

Researchers have successfully reanimated the bodies of 46,000-year-old microscopic roundworms they found frozen 130 feet below the Siberian permafrost.

Amazingly, the worms got to work right away, and started reproducing in a laboratory dish.

While that may sound like the opening act of a “Jurassic Park”-style blockbuster, the researchers say they had good reason to bring back these organisms: the hope that they could help us figure out how life could adapt to rapidly changing weather patterns and climate change.

Cryptobiosis

As detailed in a new study published in the journal PLOS Genetics, the international team of researchers described how they revived a newly discovered species of nematodes, which are slender worms that can inhabit a huge range of environments.

They found that this particular species can suspend its metabolism to enter a state called “cryptobiosis,” allowing it to survive for tens of thousands of years.

Over several experiments, the researchers “mildly desiccated” both the ancient and a more-studied control group and froze them, finding that both species were easily able to survive temperatures down to -112 degrees Fahrenheit, not unlike the survival mechanism of tardigrades.

It didn’t take much to wake them up from their suspended state — and start reproducing.

“Basically, you only have to bring the worms into amenable conditions, on a culture (agar) plate with some bacteria, some humidity and room temperature,” Philipp Schiffer, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Cologne and a co-author of the study, told Vice. “They just start crawling around then. They also just start reproducing.”

“In this case this is even easier, as it is an all-female (asexual) species,” he added. “They don‘t need to find males and have sex, they just start making eggs, which develop.”

Bring Me to Life

The research could have substantial implications for our understanding of how complex organisms can survive long periods of stasis.

“Our findings indicate that by adapting to survive [in a] cryptobiotic state for short time frames in environments like permafrost, some nematode species gained the potential for individual worms to remain in the state for geological timeframes,” the paper reads.

Given how global warming is triggering rapid changes in the environment, the researchers postulate that organisms like these nematodes could potentially be woken from their millennia-long slumber, an impressive survival mechanism that could “lead to the refoundation of otherwise extinct lineages.”

More on worms: Scientists Surprised by DNA in Worms That Control Hosts’ Brains