Hidden World

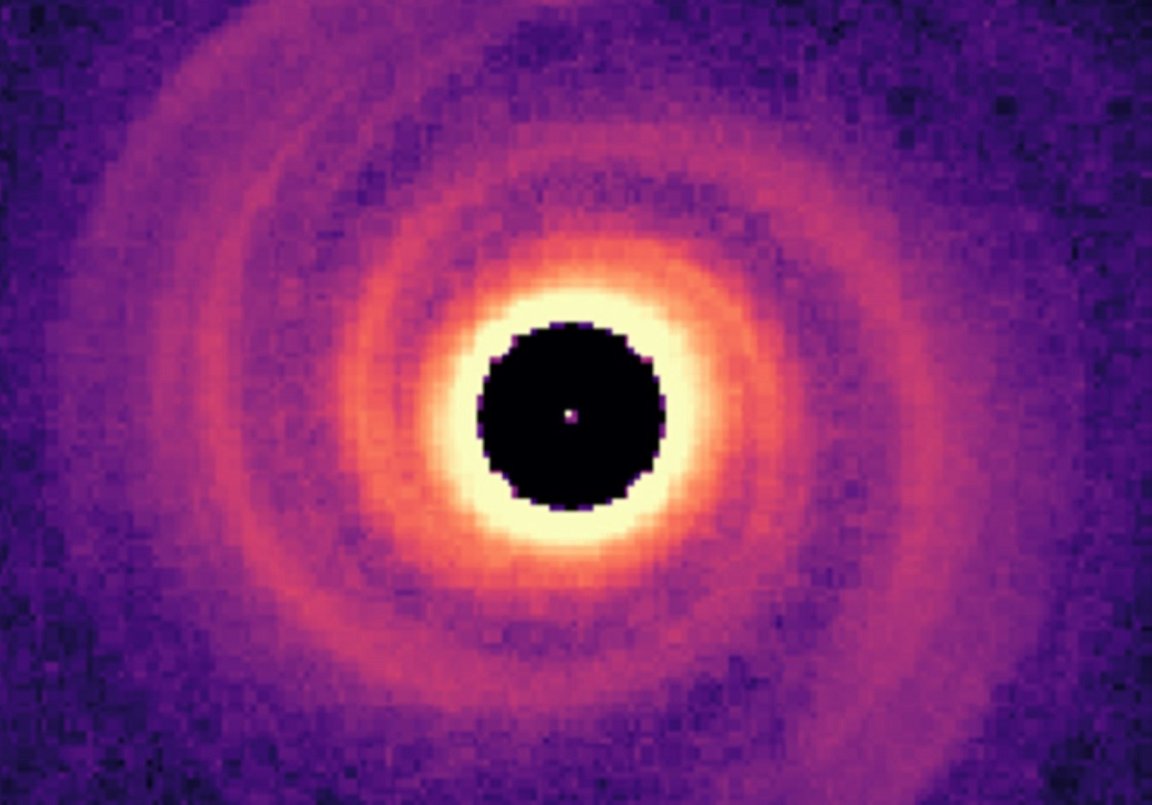

Many galaxies — including our own Milky Way — form in spiral-like shapes. But there are some curious stars out there that have spirals of their own, surrounded by what’s known as protoplanetary disks of gas and dust that can eventually form planets and other objects. These spirals have long been the source of intrigue for astronomers because of the prominent, tentacle-like “arms” that extend out of them.

And now, as reported in a new study published in the journal Nature Astronomy, astronomers have detected something fascinating within one of these spirals, surrounding a young star about 500 light years from Earth: a newborn, gas giant exoplanet. It could be the final piece in the puzzle explaining how these “arms” form in the first place.

“Our study puts forward a solid piece of evidence that these spiral arms are caused by giant planets,” lead author Kevin Wagner, an astronomer at the University of Arizona Steward Observatory, said in a statement.

Helping Arm

The be-tentacled star in question is only a couple million years old, which is why it’s still swaddled in a spiraling protoplanetary disk that will take millions of more years to break apart.

While it persists, the sheer gravity of the newly discovered exoplanet, designated MWC 758c, appears to be drawing some of the disk’s spiraling debris outward into these striking arms. At twice the mass of Jupiter, it’s a real heavyweight.

This is pretty much exactly what astronomers have theorized but until now have failed to observe — that such planets and their resulting arms would play a big role in forming potential planetary systems.

“Spiral arms can provide feedback on the planet formation process itself,” Wagner explained. “Our observation of this new planet further supports the idea that giant planets form early on, accreting mass from their birth environment, and then gravitationally alter the subsequent environment for other, smaller planets to form.”

Elusive Planets

Arguably the bigger mystery is why astronomers weren’t able to spot these nascent gas giants in the first place.

The researchers only achieved their breakthrough by using the Large Binocular Telescope Interferometer (LBTI) in Arizona to detect MWC 758c. While most exoplanet hunting telescopes scan shorter, bluer wavelengths, the LBTI scans longer, redder wavelengths in the infrared range.

That a planet appeared so red was highly unexpected, if not unprecedented. According to study co-author and LBTI lead instrument scientist Steve Ertel, it’s the “reddest” planet ever discovered.

“Either this is a planet with a colder temperature than expected,” Ertel said, “or it is a planet that’s still hot from its formation, and it happens to be enshrouded by dust.”

More on stars: If Betelgeuse Explodes, It’ll Be So Bright You Could See It During the Day For a Year