Pachelbel’s “Canon in D” is like the Doom of the music world. It’s been performed on everything from train horns to rubber chickens to strange juggling bells — it would truly be easier to find an instrument the Canon hasn’t been played on.

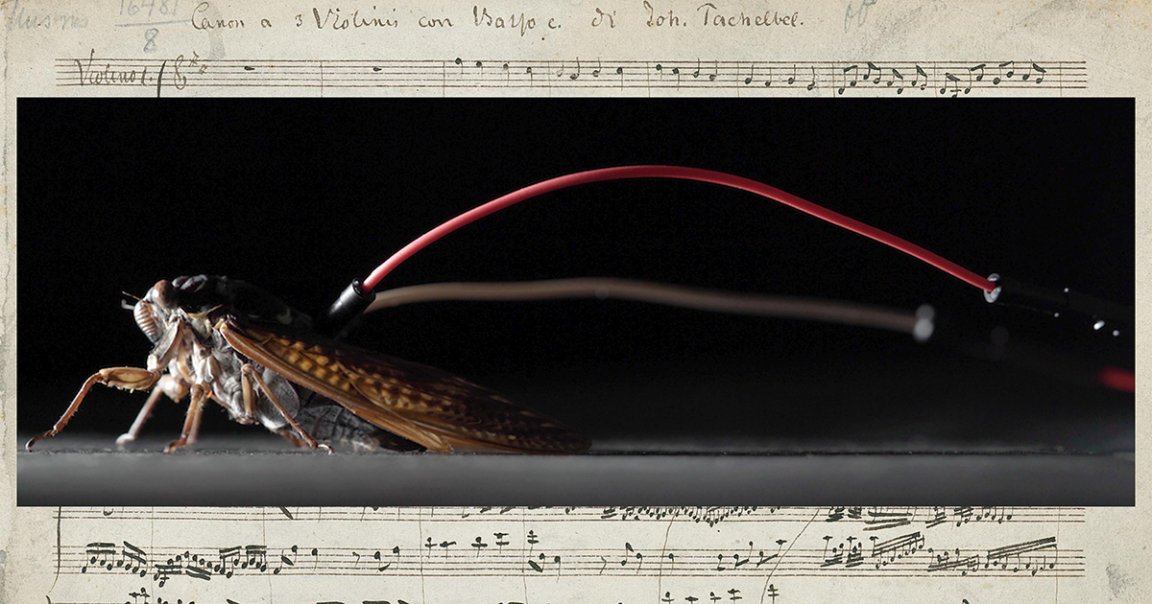

Recently, a new “instrument” entered the pantheon, only it’s not an instrument at all, but rather an insect stuck with probes and zapped with electricity. If you’re imagining the typical wedding arrangement of Pachelbel’s Canon played on a harp or string quartet, you might be disappointed, because this particular rendition uses the face-scrunching sounds of the brown cicada.

The “breakthrough” — if we’re calling it that — comes from a team at the University of Tsukuba in Japan, which stuck a choir of cicadas full of electrodes to make them sing.

The whole thing is possible thanks to the cicada’s noise organs, called the timbal. Timbals are a pair of ridged membranes located in the cicada’s abdomen. When rubbed together, they produce the insect’s infamous “songs,” which males use to attract mattes.

In the wild, male cicadas will band together in groups, coincidentally called a chorus, which can become literally deafening depending on how many of the insects join together.

In the lab, Tsukuba researchers used carefully controlled electrical signals to force the timbals together. By manipulating the voltage, the team was able to unlock the potential of the cicada chorus and grace us with the most offensive rendition of Pachelbel’s canon we’ve ever heard. They also explored which electrical waveform was best for controlling the insect’s timbals, and the pitch range at which cicadas can sing.

A video of the experiment uploaded by the New Scientist explains that the cicadas were “reproducing tones over more than three octaves” — roughly mirroring the tonal range of the standard orchestral glockenspiel.

Naoto Nishida, a University of Tsukuba researcher, noted that the critters were “relatively unharmed” by the display, with some even making it back to the wild. “Some of them wanted to run away,” he told New Scientist. “Some of them were like, ‘okay, use my abdomen.'”

Though we probably won’t see the insects at Carnegie Hall anytime soon, the researchers note the cicada’s potential for reproducing emergency audio equipment in emergency situations where energy is scarce.

More on insects: Extremely Metal “Bone Collector” Caterpillar Cloaks Itself in the Shattered Exoskeletons of Its Vanquished Foes