Red Eye

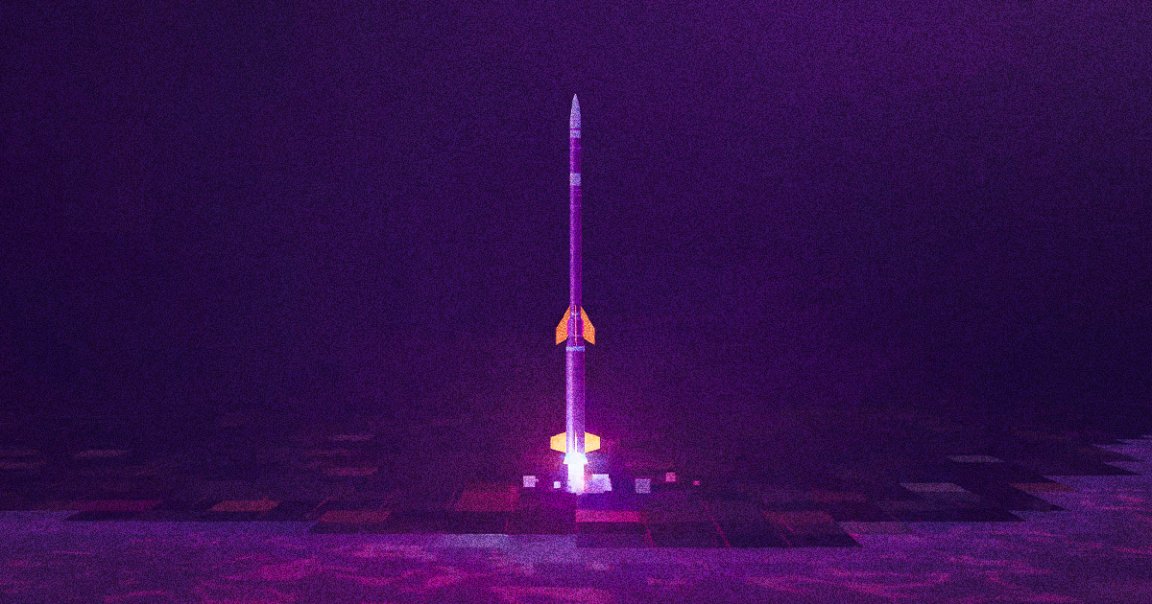

When the total solar eclipse on April 8 blankets portions of North America in shadow, NASA plans to carry out an unusual operation under cover of that momentary darkness: launching three rockets straight into the dimmed skies in hopes of understanding how the celestial event affects our atmosphere.

The so-called sounding rockets will be launched 45 minutes before, during, and 45 minutes after the eclipse to collect data on the disturbances caused to particles in an upper level of the atmosphere called the ionosphere by a total eclipse.

“It’s an electrified region that reflects and refracts radio signals, and also impacts satellite communications as the signals pass through,” said Aroh Barjatya, a professor of engineering physics at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University who is leading the mission, in a NASA release. “Understanding the ionosphere and developing models to help us predict disturbances is crucial to making sure our increasingly communication-dependent world operates smoothly.”

Catch the Wave

A solar eclipse puts the ionosphere through extreme changes in just a matter of minutes. The region, which extends about 50 to 300 miles above the Earth’s surface, goes from being warm and bombarded with ultraviolet radiation to being abruptly deprived of that energy, only to be slammed with it moments later all over again.

To some degree, that process mirrors what happens between the change from day to night. During the day, the sun’s ultraviolet radiation ionizes, or electrically charges, particles in the atmosphere that lose their electrons. At night, those particles fizzle out, regain their electrons, and become electrically neutral again.

But with an eclipse, that cycle is drastically accelerated, creating “waves” that can ripple through the ionosphere and cause disruption to radio and satellite communications. If we’re to understand the chaos that creates, scientists will have to get a close-up look at what’s going on up there.

Three’s a Crowd

The three rockets, which were used in a similar mission during a partial eclipse in October, will be launched from NASA’s Wallops Flight Facility in Virginia, reaching a maximum altitude of 260 miles. Once up there, they’ll take measurements on neutral and charged particle density.

“Each rocket will eject four secondary instruments the size of a two-liter soda bottle that also measure the same data points, so it’s similar to results from fifteen rockets, while only launching three,” Barjatya said.

Rockets are favored here because the other obvious choice of spacecraft, satellites, may not be in position to make observations during the slim window of the solar event, let alone its peak. But the NASA scientists will be backed up by ground-based observations, too, conducted at various observatories across the US. With all that data, we may finally shine a much needed light on what happens when our atmosphere is suddenly thrown into darkness.

“We are super excited to relaunch them during the total eclipse, to see if the perturbations start at the same altitude and if their magnitude and scale remain the same,” Barjatya said.

More on NASA: Debris From NASA Smashing Asteroid Could Strike Mars, Scientists Find