Mooncano

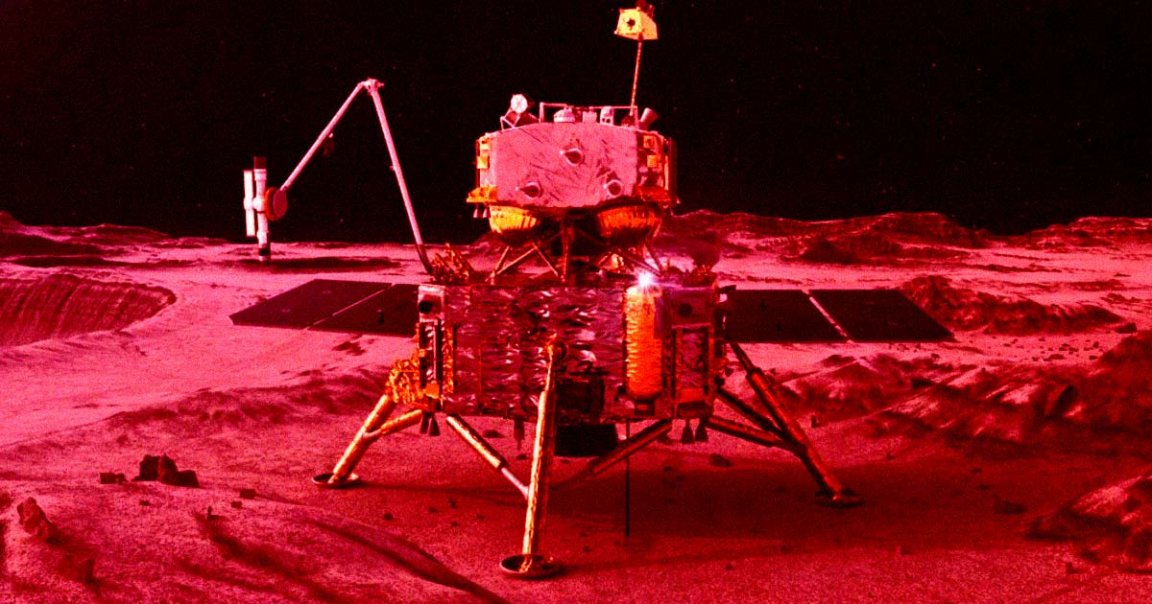

While working their way through the collected bounty of China’s Chang’e 5 lunar sample return mission, scientists made a fascinating discovery.

Tiny glass beads brought back by the lander in late 2020 suggest the Moon could still be volcanically active today, with the last eruption taking place an estimated 123 million years ago.

While that may sound like a lot, it’s a mere blip in the geological history of the Moon, and far more recently than previously thought, potentially upending scientists’ current understanding of its evolution.

The findings could also shed new light on how small planets and moons can stay volcanically active over many millions of years.

Bead It and Weep

In 2014, observations by NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter suggested that the Moon’s volcanic activity may have slowed gradually. Distinctive rock deposits led scientists to speculate that the Moon may have been volcanically active less than 100 million years ago, around the time dinosaurs were roaming the Earth.

China’s Chang’e 5 samples, however, which are the first lunar samples to be returned since the 1970s, represent the first physical evidence of the Moon’s recent and possibly ongoing volcanism.

As detailed in a paper published in the journal Science, scientists believe that just three out of the 3,000 glass beads recovered in the samples were formed by a volcanic eruption. The rest of them, they believe, were more likely to have been formed by an asteroid impact.

The surprising findings are in contrast to existing theories that by dinosaur times the Moon had already cooled down to the point where it was no longer possible for these beads to form.

“These three glassy droplets are the first physical evidence we have for anomalously recent volcanic activity on the Moon,” wrote Lancaster University professor Lionel Wilson, who was not involved in the research, in a piece for The Conversation, adding that “these findings could prompt a major revision in our understanding of how the Moon developed.”

“It should inspire lots of other studies to try to understand how this could happen,” Lunar and Planetary Institute senior staff scientist Julie Stopar, who was also not involved in the research, told the Associated Press.

More on the Moon: Chinese Scientists Working on Magnetic Launch System to Fling Cargo From Moon’s Surface Back to Earth