Spray-On Nanomaterials

A new printing technique, developed by research teams from the NASA Ames Research Center and the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, makes it possible to print miniature devices and nanoelectronics onto objects normally too delicate to survive the printing process.

It means the development of inexpensive, easily produced, wearable nanosensors for chemical and medical purposes, not to mention a host of other applications, such as “smart clothing,” and even the ability to realize the dream of “programmable matter” and the “Internet of Things,” by incorporating electronic sensors and devices into ordinary objects such as paper, pens, fabrics, and just about anything else.

Welcome to the dawning of the age of printable nanomaterials.

Formerly, nanomaterials were printed using a basic inkjet-type printer—the materials were injected into an “ink” of some sort, and then lacquered onto an object that had to be loaded like paper. The limitations are obvious, and the need for a liquid “ink” ruled out certain materials. It’s possible to print some nanomaterials as aerosols, but this required additional heating to several hundred degrees—a process that would destroy delicate flammables such as paper or fabrics.

Enter the “plasma method.”

Plasma Printing

The new technique involves infusing a plasma of helium ions with the nanomaterials, and spraying it directly onto the surface at temperatures not much above 40° C (104° F). No extra heating is necessary, and since the process involves a nozzle that can work along 3 axes, it’s possible to print on flexible or 3-dimensional objects, in any shape or configuration.

Says Meyya Meyyappan of NASA’s Ames: “You can use it to deposit things on paper, plastic, cotton, or any kind of textile. It’s ideal for soft substrates.”

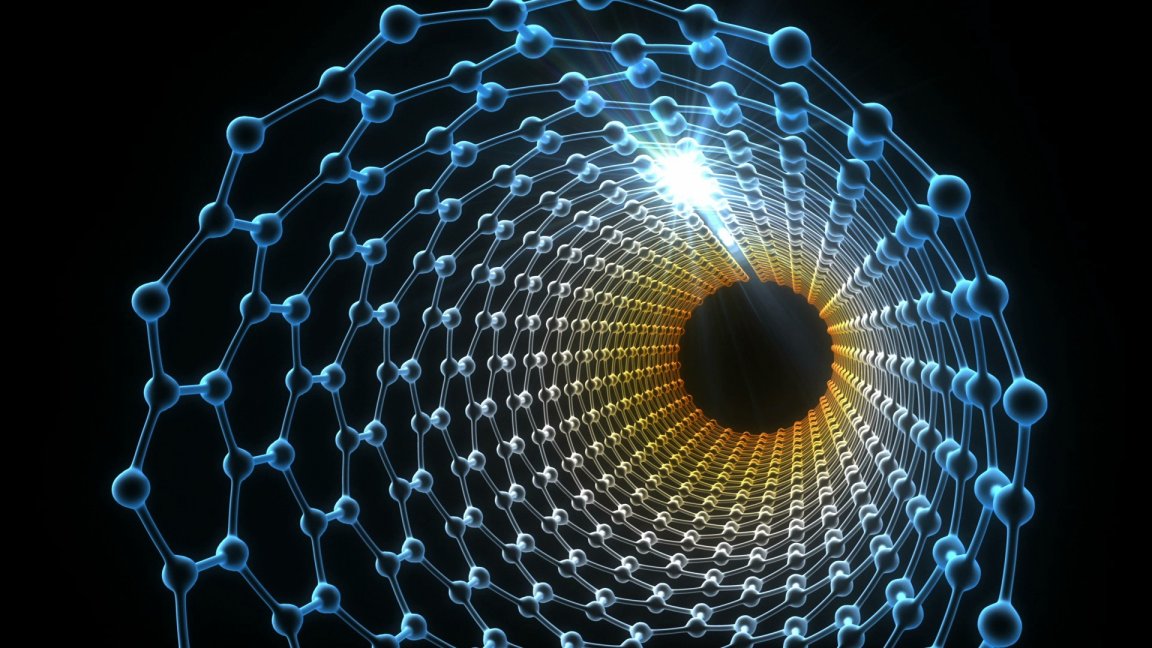

The team demonstrated by printing proof-of-concept nanosensors on a piece of paper—they used carbon nanotubes, which can react to certain molecules by changing their electrical resistance. The chemical and biological sensors were capable of detecting, respectively, ammonia and dopamine.

The method is ready for commercial application, and the team is already experimenting with further uses—for instance, manufacturing tiny batteries for smartphones.