On Sunday, a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket stuffed with cargo carried a brand new NASA telescope into space, where it was observed deploying in Sun-synchronous orbit, the agency later confirmed.

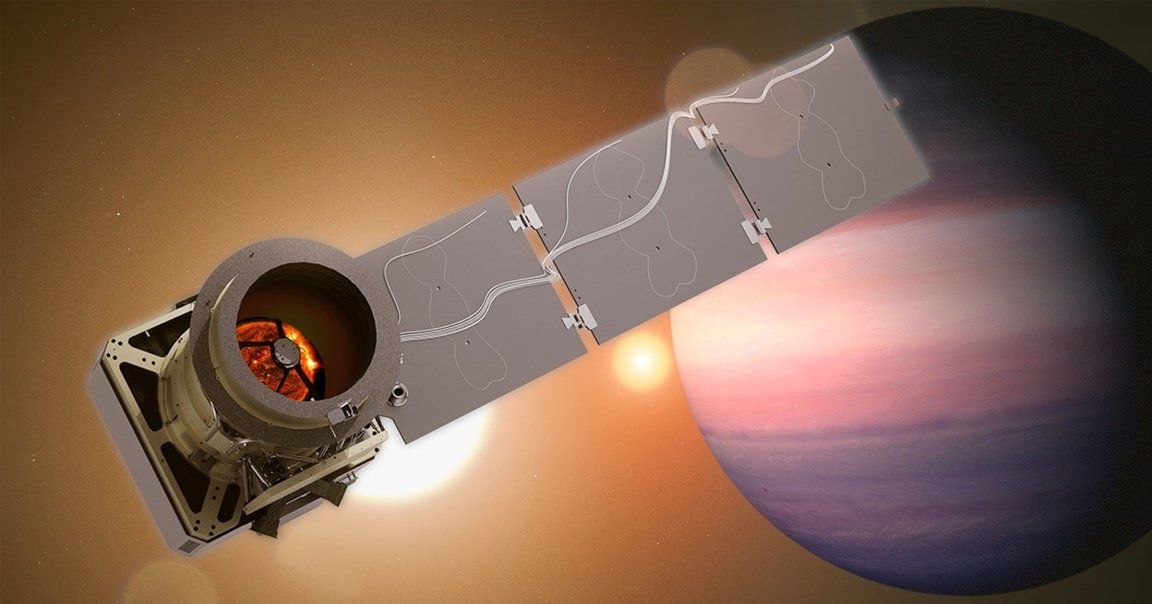

Dubbed Pandora, the orbital observatory is designed to hunt for distant worlds called exoplanets orbiting other stars. And though not nearly as large or expensive as the James Webb Space Telescope, the 17-inch lens packs a specialized punch that’ll help astronomers do something that was unthinkable just a decade or two ago: glean clues from individual exoplanets too remote for even the mighty Webb to pick up on.

Pandora’s mission will last a year, during which it’s expected to complete observations of at least 20 exoplanets — as well, in a novel development, of the stars they orbit.

This will “shatter a barrier,” according to University of Arizona astronomer Daniel Apai, whose team helped build the telescope — helping “remove a source of noise in the data that limits our ability to study small exoplanets in detail and search for life on them,” he wrote in a new piece for The Conversation.

Exoplanets are incredibly difficult to find, and even harder to study. Look up into the night sky, and you will effortlessly spot millions of stars. The first exoplanet, in contrast, wasn’t confirmed until 1992; to this day, astronomers have found only around 6,000 planets around other stars, a task hindered because the little-if-any light they reflect is blown out by that of nearby stars.

To espy distant worlds, astronomers look for when a planet passes in front of its star from our perspective. This is called a transit, and it produces a noticeable dip in the starlight. What’s more, astronomers can analyze the light to tease out properties of the planet it passes through, like the chemicals in its atmosphere. Apai, who is also co-investigator of Pandora, compares this to holding a glass of wine up to a candle: “The light filtering through will show fine details that reveal the quality of the wine.”

Likewise, “by analyzing starlight filtered through the planets’ atmospheres,” he continued, “astronomers can find evidence for water vapor, hydrogen, clouds and even search for evidence of life.”

Astronomers have relied on this clever trick for decades, but recent research, some of it spearheaded by Apai and his colleagues, has shown that it can have a serious flaw. Cooler, volatile regions on the surface of stars, called starspots, can fudge the signals astronomers see, even tricking them into mistaking the water vapor around a star for being present on the planet. Essentially, “we were trying to judge our wine in light of flickering, unstable candles,” Apai said.

That’s where Pandora comes in. Being purpose-built for exoplanet hunting, it can spend far more time observing them than Webb, whose precious time is always in hot demand. Even better, Pandora will observe the stars themselves for 24 hours at a time with infrared and visible light sensors, closely monitoring how the starspots form and evolve. Over the course of its year-long mission, the telescope will revisit each star ten times, racking up hundreds of hours of observations.

“With that information, our Pandora team will be able to figure out how the changes in the stars affect the observed planetary transits,” Apai wrote.

More on exoplanets: James Webb Discovers Planet Shaped Like Lemon