AN ATOMIC SANDWICH

Experts may have just found a way to create a material that allows for greater computing power with less energy input. In a paper published in Nature, a collaboration of researchers from Cornell University and the University of Michigan reported a magnetoelectric multiferroic material, which exhibits room-temperature electrical and magnetic properties.

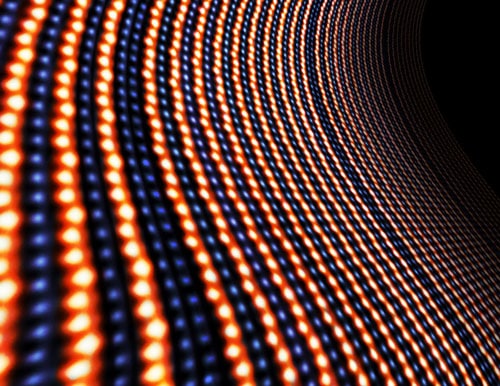

According to a report by the University of Michigan News, the team used lutetium iron oxide (LuFeO3) in the study, precisely because it was composed of alternating layers of iron oxide and lutetium oxide. Afterwards, an extra layer of iron oxide was added every ten repeats of a unique single-single pattern (see image). This was done to facilitate, at room temperature, a phenomenon called “planar rumpling,” which utilizes the rumples—infinitesimally small displacements—that already exist in lutetium to move a proximate layer of iron oxide’s magnetic field (from positive to negative, or vice versa) by simply applying an electric field.

Because the material already displays electrical and magnetic properties at room temperature, it will require significantly less energy to power up and keep running, as opposed to current devices that use semiconductors. New devices developed with this material would no longer need a constant stream of electricity; just quick bursts, using whopping 100 times less energy.

MORE FOR LESS

Although it may take time before actual devices run by room-temperature multiferroics hit the market, the study provides significant insight in developing faster electronics with lower power consumption.

This proves ever more important, as Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory associate director for energy technologies Ramamoorthy Ramesh believes that the fastest-growing user of energy all over the world is the electronics industry. In an interview, he said, “…about 5 percent of our total global energy consumption is spent on electronics, and that’s projected to grow to 40-50 percent by 2030 if we continue at the current pace and if there are no major advances in the field that lead to lower energy consumption.”