Beefing Up Corn

New research shows how, with the addition of a bacterial gene, corn’s nutritional value can be efficiently enhanced. The gene enables corn, the largest commodity crop in the world, to produce methionine, a key amino acid essential for tissue repair and growth. By producing a staple crop that contains methionine, which is found in meat, millions of people all over the world who can’t afford to eat meat could improve their health through nutrition. This genetically engineered corn crop could also dramatically reduce worldwide animal feed costs.

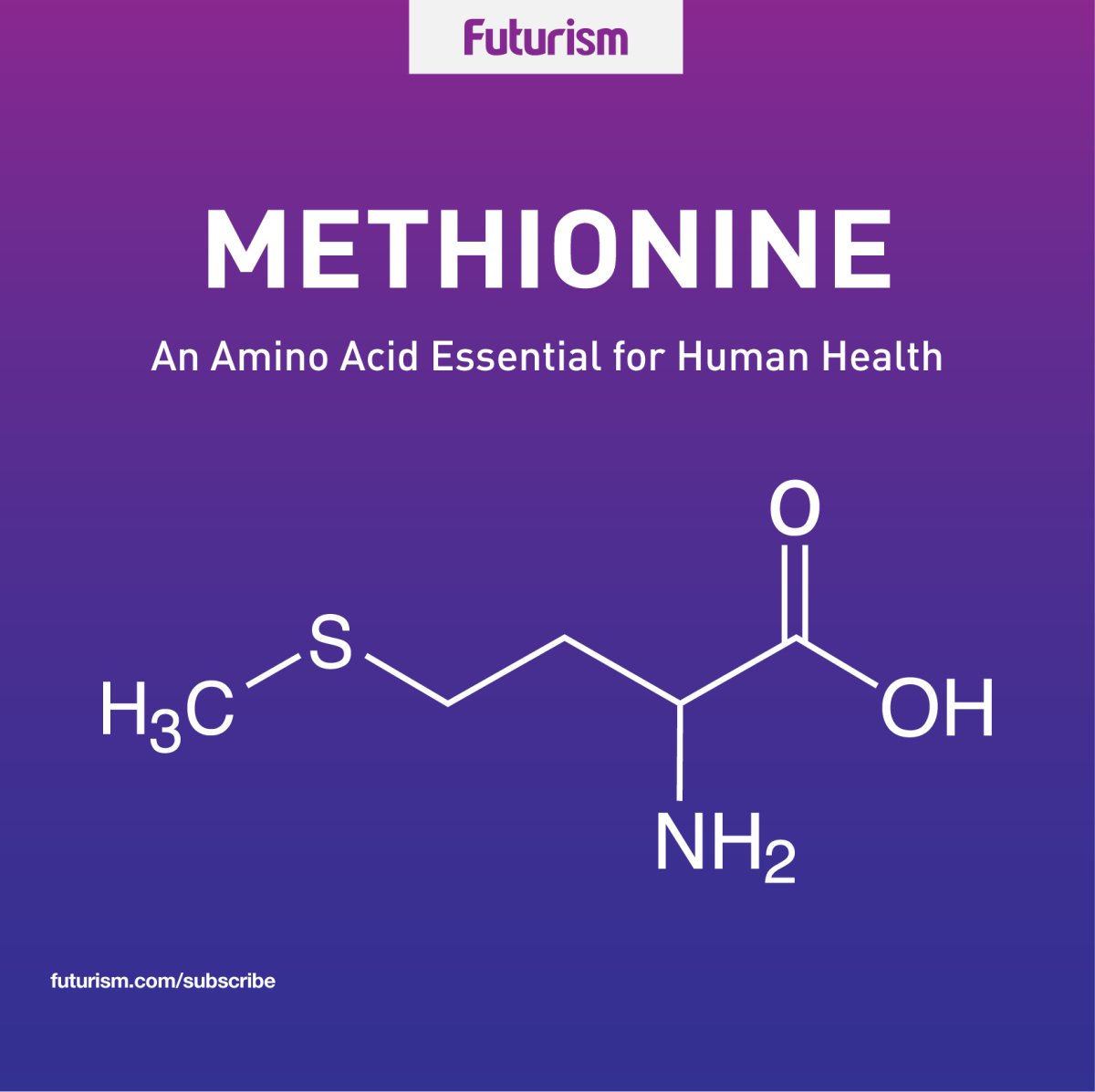

Methionine is one of nine amino acids that are essential to human health. In addition to supporting tissue repair and growth, it strengthens nails and improves the skin’s flexibility and tone. Methionine also contains sulfur which aids cells in absorbing zinc and selenium, and guards against both pollution and premature aging. Amino acids occur in our food, so nutritionally inadequate diets often lack sufficient amounts of one of more of these critical compounds.

Animals, including livestock, also need methionine. This means that billions of dollars’ worth of methionine must be added to field corn seed annually, since corn lacks the amino acid in nature. For example, according to the study, chicken feed is typically made up of corn and soybeans, so it is typically lacking methionine, the essential sulfur-containing amino acid.

“It is a costly, energy-consuming process,” Waksman Institute of Microbiology director and study senior author Joachim Messing said in a press release. “Methionine is added because animals won’t grow without it. In many developing countries where corn is a staple, methionine is also important for people, especially children. It’s vital nutrition, like a vitamin.”

Adding Methionine to Corn

Within this study, researchers inserted a gene from the E. coli bacterium into the genome of the corn plant and then produced several generations of the modified corn. The E. coli enzyme — 3?-phosphoadenosine-5?-phosphosulfate reductase (EcPAPR) — spurred methionine production in the leaves of the plant rather than throughout the plant. This was an intentional choice, with the aim of avoiding an accumulation of toxic byproducts. It was enough to prompt a 57 percent increase in methionine in the corn kernels, and observations of chickens who ate the corn as part of a feeding trial showed that the modified plant was nutritious.

“To our surprise, one important outcome was that corn plant growth was not affected,” Rutgers University-New Brunswick Department of Plant Biology professor and study co-author Thomas Leustek said in the press release. This will be a tremendous boon to subsistence farmers in the developing world, Leustek pointed out: “Our study shows that they wouldn’t have to purchase methionine supplements or expensive foods that have higher methionine.”

This is another example of the ways that genetically modified foods can actually be helpful from a public health perspective, despite the generally negative reputation they endure. Scientists are focusing on food to help farmers grow more food efficiently and with a decreased environmental impact. The important thing to note from this research is that we should remain vigilant about the long-term effects of our actions, and not let blanket fears stand in the way of progress.