A team of bioengineers have created a “vagina on a chip” to mimic key features of the vaginal microbiome, The New York Times reports.

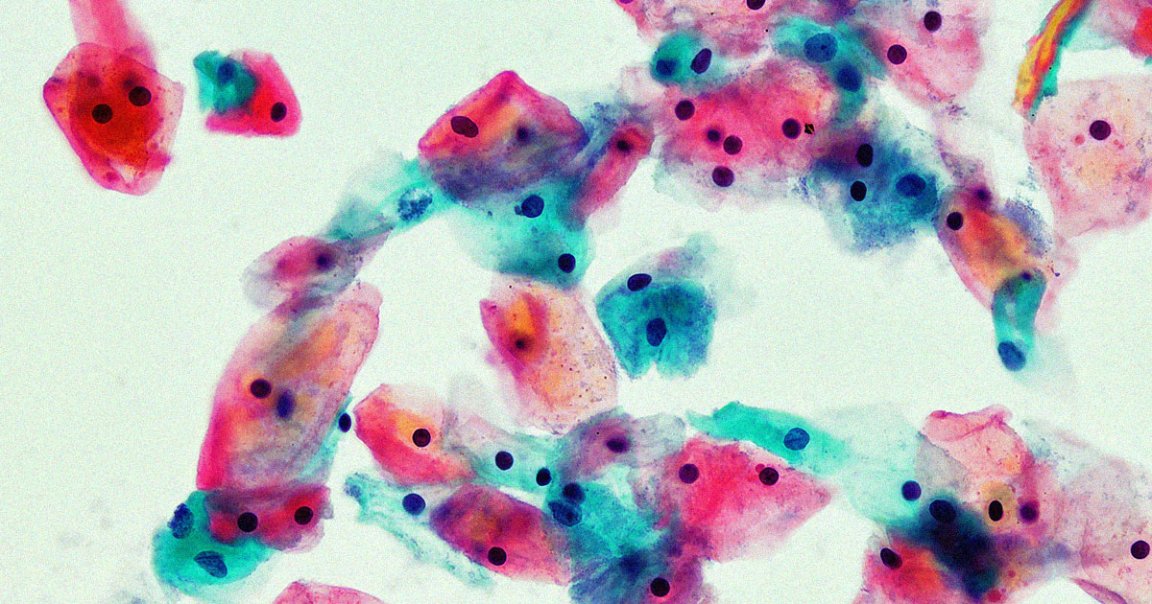

This simulated “organ chip,” made from donated vaginal cells, allows scientists to study the complex interactions between the vagina’s cells and fluids, as well as testing treatments for bacterial vaginosis, a common microbe infection which affects around 30 percent of women.

The research is particularly important, as the human vagina remains severely understudied by scientists. Women’s sexual health has historically been vastly underrepresented in the scientific community, particularly when compared to men’s sexual health.

To this day, consequently, our understanding of the vaginal microbiome is surprisingly limited.

But as detailed in a study published last month in the journal Microbiome, the vagina on a chip successfully allowed scientists to study the interaction between changing levels of estrogen hormones and bacteria. It’s the most realistic lab model of the organ to date, according to its creators.

“This walks, talks, quacks like a human vagina,” Don Ingber, and a bioengineer at Harvard and co-author of the paper, told the NYT.

Ingber and his colleagues have previously created other organ chips, simulating the human lung, liver, and intestines, among others.

Testing new medications for the treatment of bacterial vaginosis, inflammation caused by invading harmful bacteria, can be tricky as it’s difficult to find willing participants for studies, according to experts.

Worse yet, the inflammation is difficult to treat, as even antibiotics aren’t a permanent solution. Bacterial vaginosis also increases the risk of sexually transmitted infections, as well as cervical cancer, according to the NYT.

Enter the vagina on a chip. During tests, the simulated organ’s tissues responded positively to bacteria that create an acidic and therefore protective environment.

Three-dimensional organ chips made of donated tissues have plenty of advantages of other in vitro models. In a two-dimensional petri dish, bacteria usually end up killing the cells very quickly making these interactions almost impossible to study.

Despite these latest efforts, scientists still have a lot to learn about the vagina.

“We don’t really understand how these processes are triggered by bacteria in the vagina or often even which bacteria are responsible,” Amanda Lewis, a professor at the University of California, San Diego, who was not involved in the study, told the NYT.

“As you might imagine, such a crude understanding of such an important physiological system makes for crude interventions or none at all,” Lewis added.

The scientists are now working on even more complex organ chip models that could allow them to test how the vaginal microbiome responds to other diseases, important research that could finally fill the many glaring gaps in our understanding of the vagina.

READ MORE: Scientists Have Designed a ‘Vagina on a Chip’ [The New York Times]

More on the vagina: New Sex Toy Aims to Emulate the Experience of Having a Penis