IN THE LAST YEAR, at least 30 men have made an appointment with an orthopedic surgeon named Dr. Kevin Debiparshad to have him saw through their perfectly healthy leg bones.

At his LimbplastX Institute in Las Vegas, Debiparshad cuts through patients’ femurs or tibias, forces the bones to separate with metal implants, and sends them on their way to heal. Once their bones grow back, they’ll be several inches taller — like that one scene in the 1997 sci-fi film “Gattaca.”

“It’s no secret that taller men have an advantage when it comes to dating,” reads a LimbplastX Institute press release. “In the age of digital matchmaking, the desire to appear taller has gained prominence, particularly for men with below-average height.”

When Futurism spoke with Debiparshad, he dismissed the press release as marketing hyperbole — though he didn’t quite rule out dating as a motivation for leg-extension surgery.

“I don’t think [dating is] the main reason people do that,” he said. “I certainly see that, and I don’t think it’s less of a reason. If you feel unconfident, I can change that. Sometimes one or two inches makes a world of difference.”

That world of difference, however, comes with an outrageous price tag: Leg extension surgery at the LimbplastX Institute can run customers over $100,000, limiting the clientele Debiparshad sees to the very rich and, probably, the very insecure.

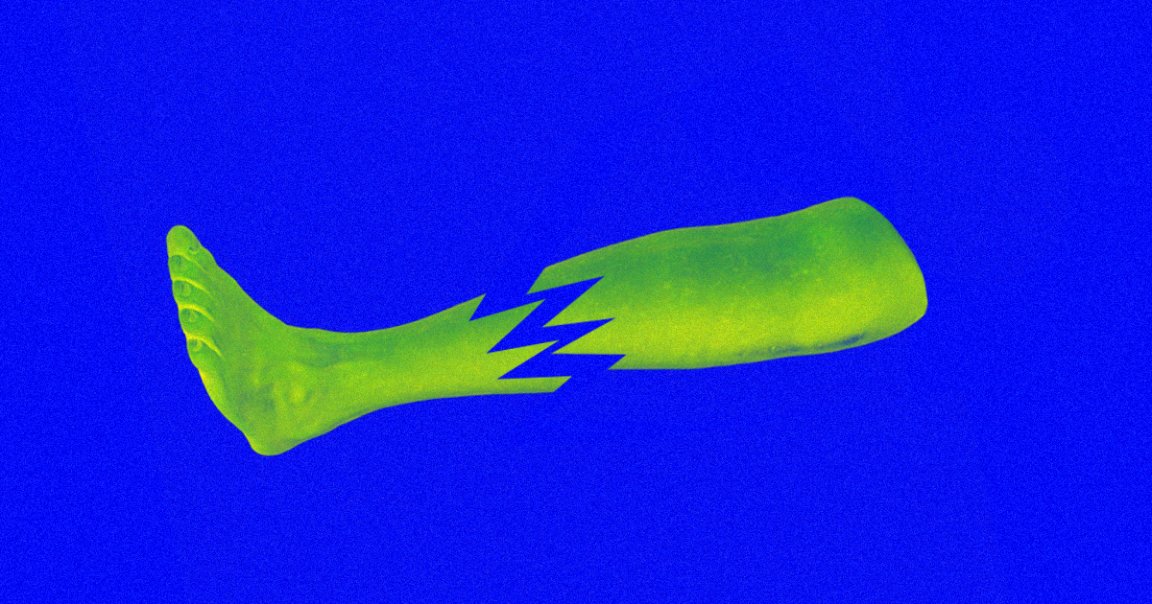

Officially called distraction osteogenesis, the leg extension surgery involves cutting either the femur, tibia, or both, and using metal braces to extend the bones. Over time, new bone cells will grow, effectively making each leg up to three inches longer.

For nearly a century, doctors have used it to help patients with congenital defects or after traumatic injuries — but now, it’s become the latest trend in extreme cosmetic surgery.

Leg Up

Before Debiparshad started LimbplastX in late 2018, most of his cases were for patients who needed leg extension surgery in order to walk and live normally.

If a child’s growth plates — the soft tissue that grows over time and forms new bones — are injured, one of their legs’ growth could end up stunted. The same can happen to adults who were in a car crash or had part of their bone removed to treat cancer or a serious infection. In all those cases, a leg extension could be used to balance out their legs’ lengths. For those patients, leg extension would be a necessary step toward recovery — the goal being to restore balance and symmetry rather than to walk away a few inches taller.

Most doctors who perform leg extension do so for clinical cases, and Debiparshad continues to treat those patients as well. But, as clinics like LimbplastX Institute and others emerge, leg extension has become another way for healthy people to enlist doctors to correct what they perceive to be personal flaws.

Debiparshad now compares the procedure to butt implants, nose jobs — and even, provocatively, gender reassignment surgery.

“The concept is not something that’s new, we knew we could do this for a long time,” Debiparshad said. “It’s just that now technology is catching up with what we knew we could do, so now we can push new applications.”

For private clinicians, that represents a lucrative new marketplace. But for the patients, it means tens of thousands of dollars and months of physical therapy — for insecurities that might have been healed in years past through therapy or platform shoes.

Confidence Boost

Elective limb lengthening came under newfound scrutiny in September, when Jezebel ran an essay in which the author described how her brother died from medical complications after he had his legs extended by a French orthopedic surgeon named Dr. Jean-Marc Guichet.

“We do not perform cosmetic lengthening for providing more capacity for specifically dating or getting a higher salary,” Guichet told Futurism in an email. The main goal, he said, “is to increase confidence and self-esteem of patients. Some males are telling me that they are not taken seriously due to their height. They perceive it as decreasing their social and work capacity, for instance when they are top managers. Some short women also have the same problem.”

But experts aren’t quite sold on the procedure.

Dr. Laura Cabrera, a bioethicist at Michigan State University’s Center for Ethics & Humanities in the Life Sciences, didn’t mince her words, arguing that cosmetic leg extension was indefensibly frivolous.

“Even if people are paying out of pocket for these interventions, you’re still consuming time of experts who are doing this for non-medical purposes,” she said. “You’re consuming time and materials that could be used for people who really need these types of interventions.”

About those out-of-pocket payments: Extending femurs — those are the upper leg bones — at LimbplastX will cost someone about $75,000. A tibia extension will run them $79,000. Afterward, the optional procedures to remove the metal implants cost up to $34,000 on top of that.

Cabrera also shared concerns regarding how patients are selected, educated, and evaluated before going under the knife.

Patients must be made to understand the risks and limitations of the procedure, Cabrera said, and ought to be evaluated to make sure that they have a reasonable understanding and expectation of what the procedure can do for them.

Both surgeons, Debiparshad and Guichet, told Futurism that they hold extensive meetings with patients to evaluate whether they’re prepared for the procedure. Both said they’ve turned prospective patients away when red flags emerged.

“The reality of a lengthening procedure needs to be known and understood and we need to evaluate the real root of the need,” Guichet told Futurism.

“Some focus needs to be made about the psychological complications. When patients are unstable or have no realistic expectations nor clear understanding of the procedure, they have some difficulty to judge what is good for medical purposes,” he added. “Some have the tendency to deviate from recommendations. This induces a lower functional result and eventually complications.”

Height Plight

Even some men who are already tall are pursuing and getting approved for the procedure. When Insider profiled Debiparshad, the article included a patient’s before and after pictures. The man was nearly six feet tall beforehand, Debiparshad said — a far cry from the “ideal patient” portrait of short men who might be overlooked at work due to their stature.

“He was one of our taller patients — he was a very reasonable guy. He’d been thinking about it for a long time,” Debiparshad said. “We spent a long time discussing. His whole thing was to be over six foot.”

Debiparshad went on to explain that he wants to make sure that prospective patients have reasonable expectations — specifically about how added height will benefit them personally, professionally, and romantically — and if they seem willing to do the necessary rehabilitation work when it comes time for physical therapy.

“On dating apps and stuff, women will literally say don’t swipe right unless you’re over six foot,” Debiparshad said. “For him, he felt romantically limited. It’s no different than why women and men get rhinoplasty, Botox. But as long as they have an understanding of what they have to go through, what the risks are and stuff, I think it’s reasonable.”

Because his services are so expensive, Debiparshad says his cosmetic patients come in well-educated and tend to have realistic goals and expectations for what the procedure can do for them. He spoke at length about how much he appreciated patients who understand the surgery’s limitations and who he could trust to complete the full rehabilitative regimen of physical therapy.

“I think this, like butt implants and stuff, will be more common in that world. I think that’s something that’s so powerful too — people will always be three inches taller or whatever you made them,” Debiparshad said. “They’ll die and be in their casket and decompose three inches longer. It’s very permanent.”

“I think that this may be more expensive, but it’s a very permanent result and it can never be taken away,” he added. “I’ve not had one patient who’s regretted having it done.”

Informed Consent

Even so, Debiparshad says he’ll sometimes refer prospective patients for a psychological evaluation.

But Cabrera argued that should be the bare minimum before going ahead with a leg extension. She said that from a medical ethics perspective, a third party who’s separate from the surgeon and their clinic would ideally be conducting the patient interviews, evaluations, and informed consent procedures.

“The problem with informed consent in general is that most people will accept things when they think those things will help them, that’s a problem with the bias in humans,” Cabrera said. “We focus on the things we want to focus on, we don’t pay attention to the other things.”

It’s certainly possible that leg extension will become more commonplace and accessible, and that the people who have it done will walk away with genuinely improved lives. Debiparshad’s cohort of happy customers can’t be dismissed. But, as with any emerging medical procedure, extra care must be taken in the earliest days to lay the groundwork for a future in which the surgery is offered as responsibly and ethically as possible.

With just a few clinics performing the procedure, overarching regulations are few and far between. Correcting congenital defects in children is a long-established practice, but because a small number of doctors offer leg extension for cosmetic purposes, they’re each basically establishing their own best practices without unifying guidelines.

Because the clinics that profit off the surgery are the same ones figuring out the rules, Cabrera says, ethical quandaries will abound.

“It’s kind of saddening to see how doctors are trained in most medical schools,” Cabrera said, “they’re told about the Hippocratic Oath, yet they still do these procedures for money.”

“For clinicians, they need to think about what is the role of physicians in modern times,” she added. “Have we accepted that cosmetic medicine is something clinicians should be doing? Or should we separate them and not call people who do these procedures clinicians?”