If you imagine life in the distant past as idyllic, think again. In grim new findings, scientists have found evidence that our ancient human ancestors engaged in cannibalism, at least sometimes.

A new study published in the journal Scientific Reports outlines previously-unnoticed archaeological findings that imply an ancient hominin cut up and ate another in what may now be the oldest-known evidence of cannibalism — though there are still lots of questions about which Homo sapiens relative (or relatives, plural) were involved.

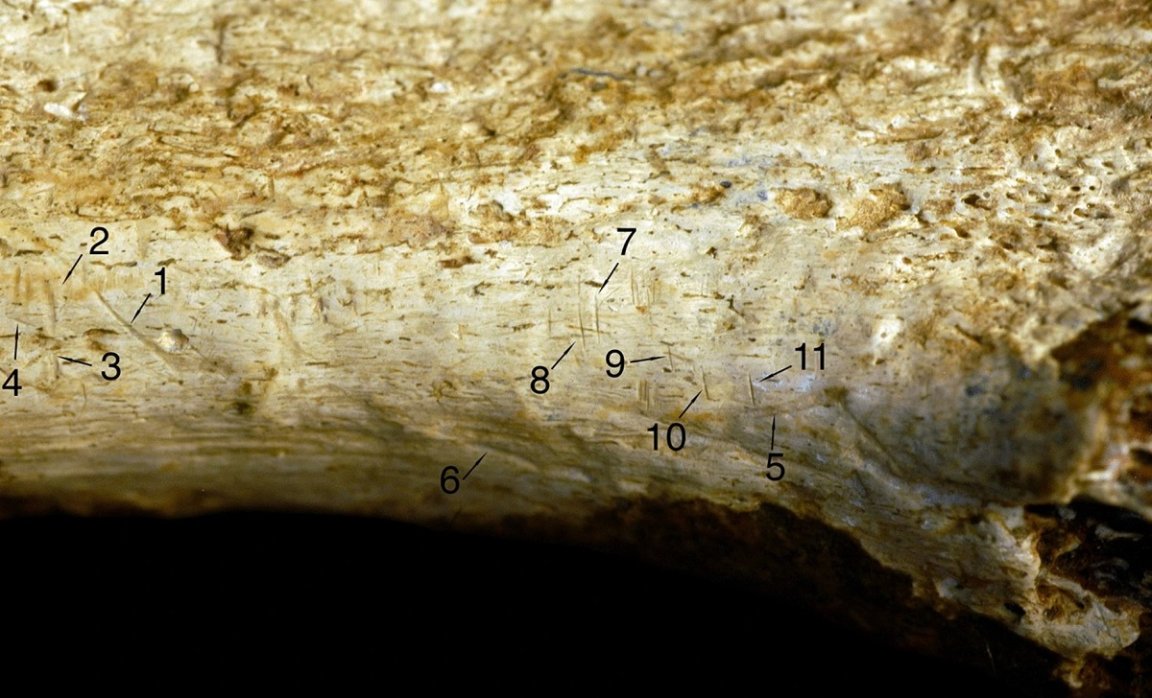

As Smithsonian magazine notes in its look at the study, these stunning conclusions came from distinctive marks on a 1.45 million-year-old shin bone that not only indicate that the bone was cut at the knee in a style used to strip meat, but also that a large cat chewed on it as well.

Beyond those facts, gleaned from remains housed in a Kenyan museum, the situation is open to interpretation, ranging from what exact species of human relative the bone is from to whether it was the same species as the ancient hominin who chopped the other up.

“We just know that some tool-wielding hominin came and cut meat off of that bone,” Smithsonian paleoanthropologist Briana Pobiner, one of the coauthors of the study, told the magazine. “The most plausible explanation is that they did that to eat it.”

Though the shin bone was found in Kenya’s Turkana region in 1970 by famous anthropologist Mary Leakey, it wasn’t until 2017 that Pobiner, who studies the evolution of human diet at the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History, took a closer look.

“I’ve seen tool marks on many animal fossils from this area and time period, so I thought, ‘Wow, I definitely know what this is,'” the researcher added. “But I also thought — ‘Surprise! This is definitely not what I thought I would find.'”

Pobiner sent data about the bone and markings to fellow paleoanthropologist — and eventual study co-author — Michael Pante at the University of Colorado to run them through a database of nearly 900 known butchery, bone, and tooth markings to see if her suspicions were right. She shared no background data about where it came from or what she believed might have gone on with the bone.

After being put through the database, according to Smithsonian‘s reporting, Pante and Purdue researcher Trevor Keevil determined that nine of the 11 markings had come from stone tools and that the two bite marks seemed to come from a big cat, which answered some questions while raising others.

The researchers behind the study have suggested that the butchered bone may have belonged to a member of the Homo erectus or Paranthropus boisei species, though there’s no consensus yet on that, much less on what of our ancestors cut it up, Smithsonian notes.

While it’s far from the first time paleontologists have found evidence of our ancestors eating each other, it’s nevertheless an incredible discovery given the sheer age of the shin bone.

“It’s interesting to think about how long our ancestors and relatives have been seeing other people as potential food,” Pobiner told Smithsonian.

More on humans consuming other humans: Youth-Obsessed Tech Mogul Now Swapping Blood With His Teenage Son