A team of researchers has kicked off the first-ever trial of a gene therapy intended to cure auditory neuropathy, a type of deafness that stops nerve impulses from making it from the inner ear to the brain.

The trial, led by Cambridge University ear surgeon Manohar Bance, will involve 18 children from across Europe and the US.

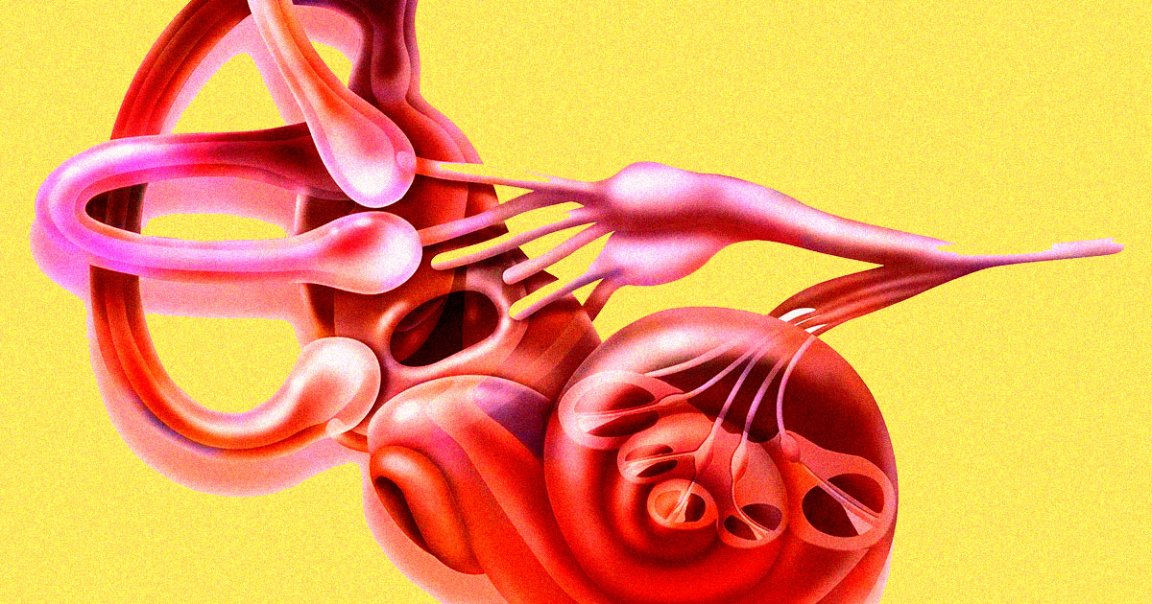

The target is a variation in a single gene called OTOF that Manohar’s team believes causes auditory neuropathy. Normally, this gene produces a protein called otoferlin, which allows inner hair cells in the ear to send signals to the hearing nerve.

But without it, these signals are never passed on to the brain, resulting in hearing loss. Roughly 20,000 people in the US, UK, Germany, France, Spain, and Italy are affected by this specific mutation, according to a press release about the trial.

“Children with a variation in the OTOF gene are born with severe to profound hearing loss, but they often pass the newborn hearing screening so everyone thinks they can hear,” Bance said in the statement. “The hair cells are working, but they are not talking to the nerve.”

“Although experimental, the therapy could also potentially result in better quality hearing compared to cochlear implants,” he added. “But

It’s not the only gene therapy solution for the varying causes of hearing loss being investigated. Researchers at Harvard University developed a drug-like cocktail that successfully regenerated hair cells in a mouse model.

And a team at King’s College in London also used a genetic approach in a proof-of-concept study earlier this year to heal deafness in mice with a defective gene impacting their hearing abilities.

The latest gene therapy approach developed by the team at Cambridge works by delivering a working copy of the OTOF gene via an engineered virus. This concoction will be delivered via an injection into the cochlea, a procedure not unlike cochlear implant surgery, which is the predominant way of treating otoferlin deficiency-related hearing loss.

Instead of having the same limitations of an implant, such as the inability to filter out background noise, the hope is that the gene therapy could address the root cause, allowing for far better results.

The ongoing trial will study both the safety and efficacy of these injections. After six months, if the gene therapy doesn’t work, the families of the participants can still opt to have their child receive a cochlear implant instead.

However, the approach does have some limitations. For one, doctors only “have a short time frame to intervene because the young brain is developing so fast,” Bance explained in the statement, meaning that it may end up being restricted to parts of the world that have sufficient access to the needed facilities.

The therapy could also end up being prohibitively expensive.

“If it works, it’s ‘one and done,'” but the cost to health systems “is something that worries me,” Bance told the Financial Times, estimating the price to be in the “million dollar range” per patient.

But if the practice catches on, “economies of scale” may lower the price over time considerably, Bance argued.

More on gene therapy: Gene Therapy Reverses Vision Loss in Primates