People in the United States sustain approximately 600,000 nerve injuries every year — and a newly unveiled biodegradable “bridge” could improve treatment for them.

The human nervous system is divided into two parts. There’s the central nervous system, which comprises our brains and spinal cords. And then there’s the peripheral nervous system, which consists of all the nerves in our arms, legs, and elsewhere that transmit signals to the central nervous system.

If one of those peripheral nerves sustains a small cut — say, a nick from a razor while shaving — the nerve can heal itself across the gap. Doctors can even repair slightly larger gaps by reconnecting the severed nerve endings.

But if an injury or illness leaves a person with a more significant gap in peripheral nerves, their only option might be an autograft. That involves a surgeon removing healthy nerve tissue from a less critical part of their body and transplanting it into the area with the damaged nerves.

Autografts aren’t ideal, because they typically only restore 50 to 60 percent of function in the damaged nerves, researcher Kacey Marra from the University of Pittsburgh told Scientific American, and they also require damaging another part of the body.

That’s where her team’s biodegradable “bridge” could help.

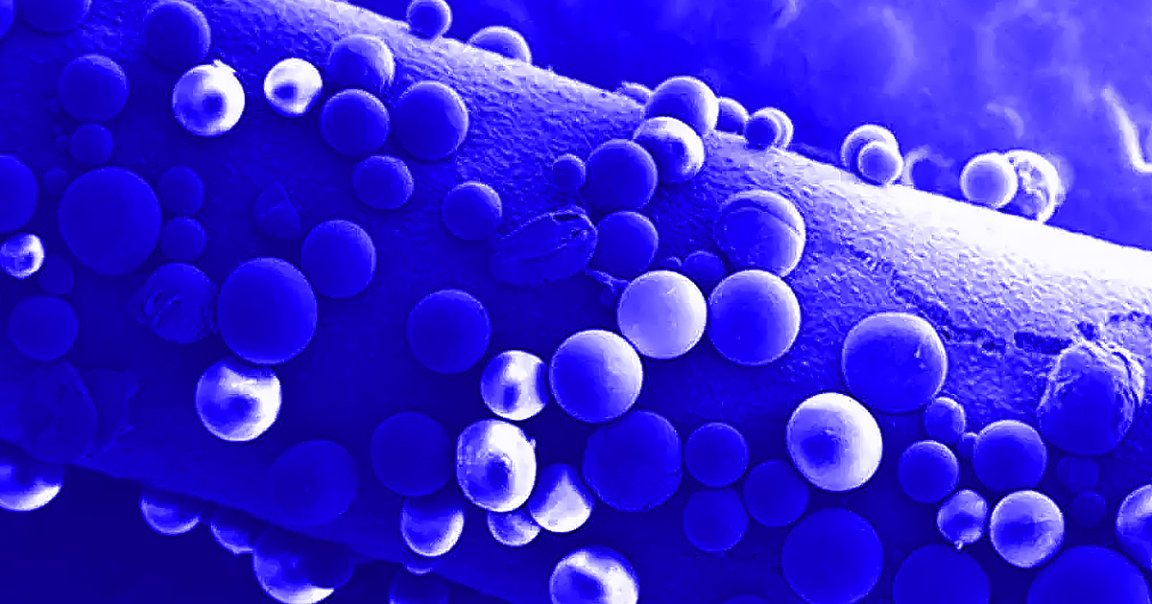

According to the team’s study, which was published in the journal Science Translational Medicine on Wednesday, the device is a tube built from the same polymer used for dissolvable stitches. Embedded in the walls of the tube are microspheres of glial-cell-derived neurotrophic factor, a protein that promotes neuron survival.

When the team implanted their device into macaques with large nerve defects in their arms, it acted as a guide for new nerve growth, ultimately restoring nearly 80 percent of function.

The tube is designed to repair nerve gaps as long as 12 centimeters (4.7 inches), and the team hopes to begin human trials in 2021. Those will take at least three years, Marra told Scientific American, but if they go as hoped, surgeons could soon have a better alternative to autografts for repairing severe nerve damage.