With few exceptions (sports, ’80s rock bands), “extreme” is something you typically want to avoid.

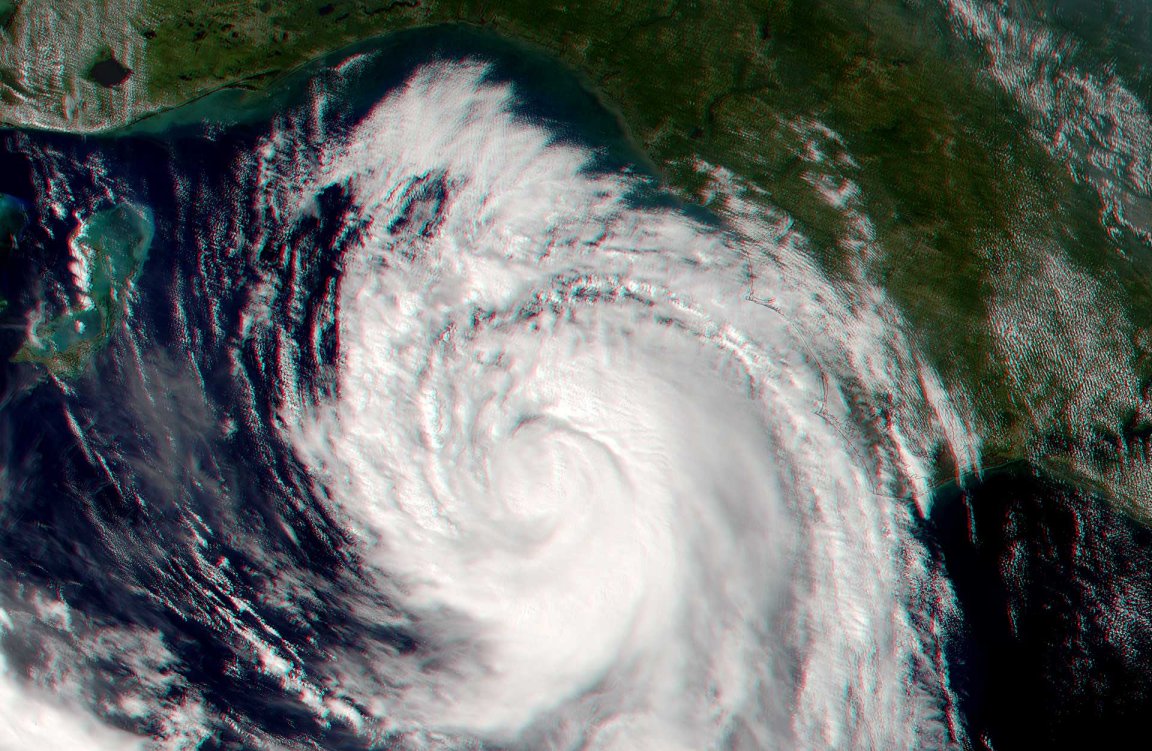

Consider, for example, extreme weather events. Floods, forest fires, and heat waves wreak havoc on our planet and, often, our economy.

Now a new report that analyzed extreme weather events has reached a disheartening (but unsurprising) conclusion: They’re happening more frequently. But the news isn’t all bad — we may be getting better at lessening their economic impact.

In 2013, the European Academies’ Science Advisory Council (EASAC), a group of 27 national science academies in Europe, released a study titled “Trends in Extreme Weather Events in Europe.” This week, EASAC shared an update to that study that incorporates data from 2013 through 2017.

For the original report, the group examined extremes in temperature, precipitation, drought, and other climate-related metrics tracked between 1980 and 2016. They found that the number of global climatological events (extreme temperatures, droughts, and forest fires) has more than doubled since 1980. In the same period, the number of meteorological events (storms) has also doubled, while the number of hydrological events (floods and mass movements like avalanches and landslides) has quadrupled since 1980 and doubled since 2004.

In short: extreme weather events were happening much more frequently across the globe. The data between 2013 and 2017 indicate that they’re not likely to get less frequent anytime soon.

The updated report also looked at potential drivers of these extreme weather events, including the weakened Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC). AMOC, also known as the Gulf Stream, has slowed down as the planet as warmed, and some scientists are concerned that it could shut down altogether, which would dramatically alter Europe’s climate. The researchers behind this study can’t tell if it would ever shut down completely, but they suggest it’s best to watch it and see.

The researchers also noted the rising economic costs of events like these. For example, in 1980, North America lost $10 billion to thunderstorms. In 2015, that figure had reached nearly $20 billion.

But in Europe, though river floods have become more frequent, those financial losses are holding steady, not rising.

This may be a tiny bit of good news in a rising sea of bad. But in fact, those static costs might show that countries have implemented more protective measures, the researchers note in a press release.

That means it might be possible to successfully “climate-proof” our populated areas to limit the impact of extreme weather events. Yes, it’s expensive, and far from foolproof. But because these extreme weather events aren’t going to become less frequent, that’s good news.