A Cloud-Shrouded Mystery

The existence of supermassive black holes, with masses millions to billions of times that of the Sun, commonly exist in the centers of large galaxies like our own; but what is less understood is how such monstrous astrophysical objects came to be in the first place.

Some theories have been proposed that suggest a kind of “snowball effect”—an effect in which a black hole of more modest size, perhaps only tens to hundreds of times more massive than the Sun, grows through the steady accretion of matter from gas clouds, ripped-apart stars, or whatever else strays too near.

Another theory holds that larger black holes, between ten and a hundred thousand times more massive than the Sun, are created through stellar collisions and eventually coalescence at the centers of compact star clusters. Ultimately, it is argues that these so-called “intermediate-mass black holes” form the seeds whence the larger, supermassive varieties grow.

Problem is, no intermediate-mass black hole has ever actually been detected.

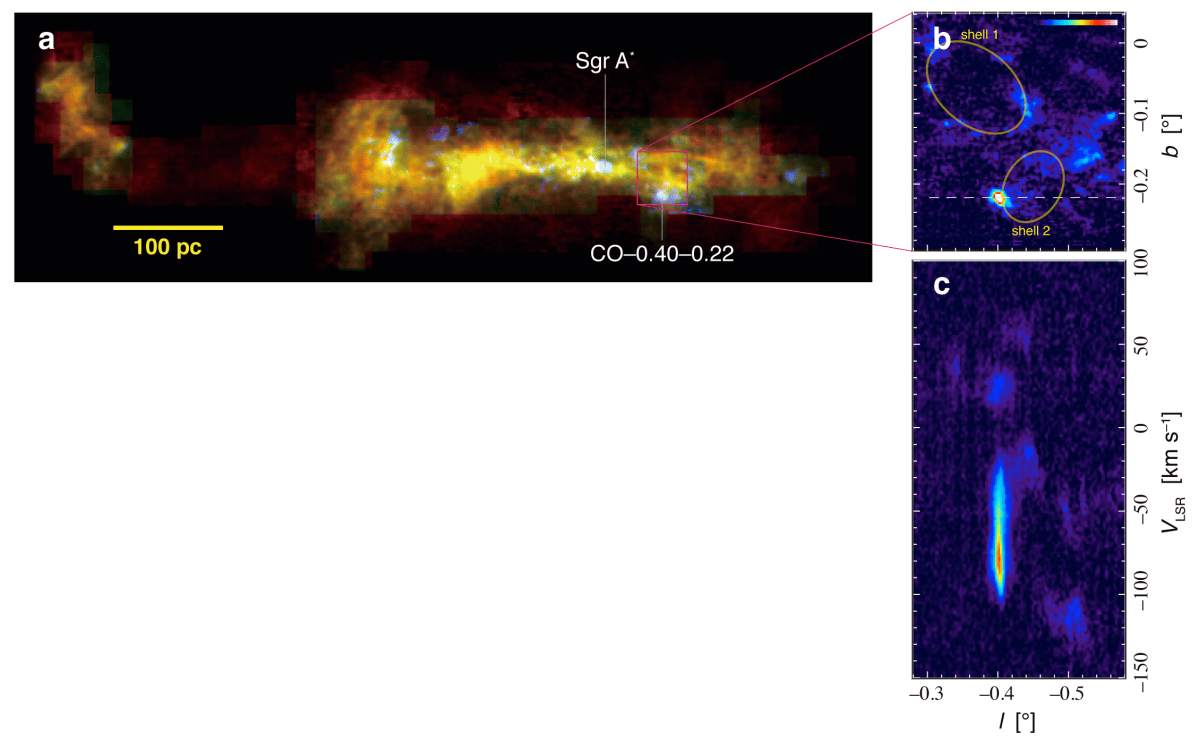

That is, until now—if the findings made by a team of Japanese astronomers, led by Tomoharu Oka of Keio University, prove correct. Using the Nobeyama Radio Observatory 45 m radio telescope, together with the ASTE telescope in Atacama, Chile, they investigated a compact gas cloud called CO-0.40-0.22, located only 200 light years from the galactic center.

What they discovered is that the cloud exhibited a curious dichotomy in the velocity of its gases: a small area of high velocity, and another, larger component with a low velocity. Further analysis in the infrared and x-ray wavelengths revealed no compact sources, suggesting the influence of something massive and invisible.

Oka and his team performed a simulation showing that a black hole of 100,000 solar masses, occupying an area with a radius of only 0.3 light years (with an event horizon about 4 times the diameter of Jupiter), best fits the observed data. In this scenario, the black hole attracts the surrounding gas, accelerating it to a high velocity at nearest approach; the material subsequently slows as its distance from the black hole increases.

“Considering the fact that no compact objects are seen in X-ray or infrared observations, as far as we know, the best candidate for the compact massive object is a black hole,” Oka observed in the original story by the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan.

The Building-Blocks of Monster Black Holes

If CO-0.40-0.22 truly does harbor an intermediate-mass black hole, it lends credence to the theory that such objects might be fairly common in large galaxies, and through accretion and coalescence gradually swell to the immense black holes that anchor the very largest galaxies.

Its proximity to the Milky Way’s central black hole, Sagittarius A*, suggests that these black holes tend naturally to sink to the heart of their home galaxies, perhaps to eventually merge with and increase their supermassive cousins (another, more modest black hole, only some 1,300 solar masses, is thought to orbit Sagittarius A* at a distance of only 3 light years).

Recent studies have shown that there are a number of other gas clouds within the galaxy that exhibit the same sort of velocity disparities as CO-0.40-0.22, indicating that there may be many more intermediate-mass black holes lurking out there…somewhere. Stay tuned for more discoveries to come.