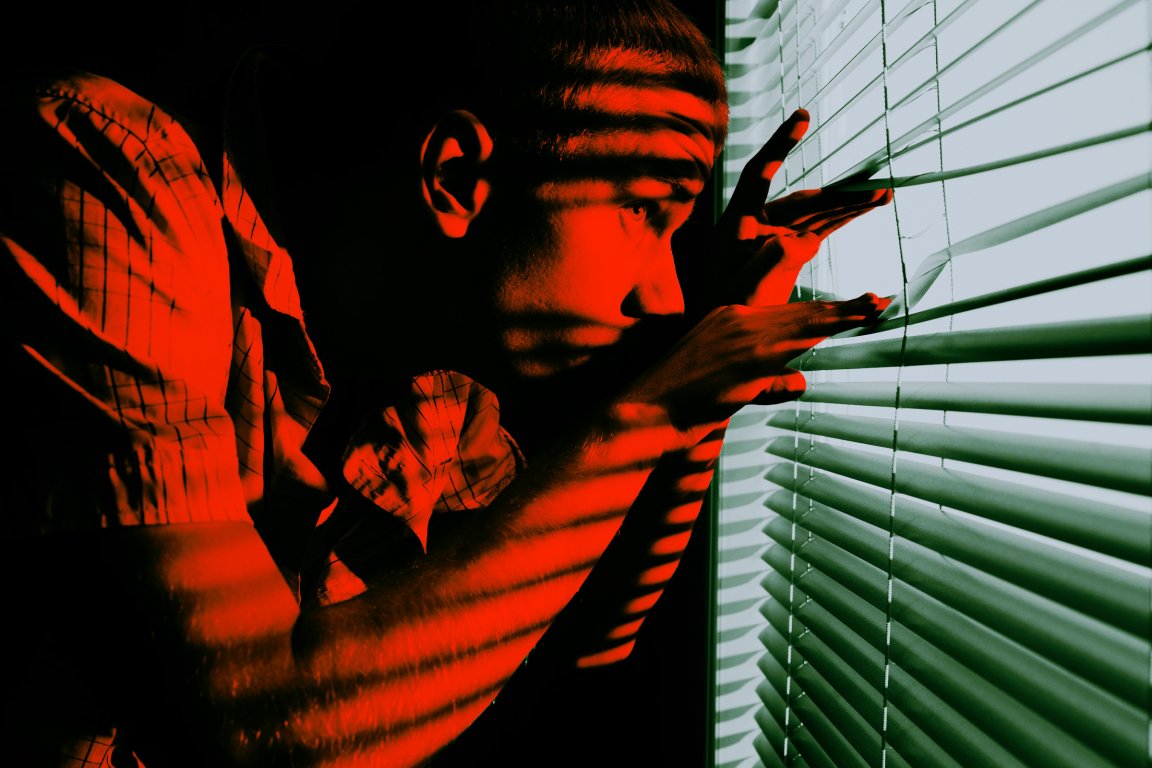

We all know that tech companies keep tabs on everything about our online habits. But it’s another thing to actually be confronted with just how much data they have on you.

This was the experience of tech journalist Pranav Dixit, who experimented with using Google’s new “Personal Intelligence” feature for Gemini and its search engine’s AI Mode. And boy, did things get personal. The AI was able to dig up everything from his license plate to his parents’ vacation history, sometimes without it being directly requested.

“Personal Intelligence feels like Google has been quietly taking notes on my entire life and finally decided to hand me the notebook,” Dixit wrote in a piece for Business Insider.

Google rolled out Personal Intelligence to subscribers of Google AI Pro and AI Ultra last week. Once you opt in, the AI can scour your Gmail and Google Photos accounts, and a more powerful version released for the Gemini app earlier this month goes even deeper, raking your Search and YouTube history, too. In short, if you’ve ever used Google for anything, it can probably dig it up.

This represents one way Google intends to keep its edge in the AI race. Unlike competitors such as OpenAI, it has decades’ worth of user data on billions of people. It can infer plenty from your Google searches alone, and your Gmail account is probably littered with confirmations and reminders for all kinds of life events, ranging from doctor’s appointments to hotel bookings to online purchases.

If the idea of letting an AI prowl through all this sounds like a privacy nightmare to you, you’re probably not wrong. Google, for its part, maintains that it’s being careful with your personal secrets, with VP Josh Woodward insisting in a recent blog post that it only trains its AI on your prompts and the responses they generate — not stuff like your photos and emails.

“We don’t train our systems to learn your license plate number,” he summarized. “We train them to understand that when you ask for one, we can locate it.”

Whatever the ethics, Dixit’s estimation is that giving the AI access to your data at least makes for a genuinely useful — and “scary-good,” in his phrasing — personal assistant.

When asked to come up with some sightseeing ideas for his parents, Personal Intelligence correctly inferred that they’d already done plenty of hikes on previous trips to the Bay Area, and suggested some museums and gardens instead.

Gemini told Dixit that it had deduced this from “breadcrumbs” including emails, photos of a forest they trekked in, a parking reservation in Gmail, and a Google search for “easy hikes for seniors.” It also figured out his license plate number based on photos stored in his Google library and scanned his emails to correctly report when his car insurance was up for renewal.

Privacy isn’t the only concern that the feature raises. With the data, chatbots can sound more humanlike, giving the impression that they’re intimately familiar with users’ personal lives. This is a dangerous road to go down amid reports of many people falling down delusional mental health spirals as they come to believe the AIs are trustworthy companions; Dixit touches on this when he complains about how’d he’d “pour my soul into ChatGPT and get a smart answer,” only for it to “forget I existed like a genius goldfish.” Experts have focused on ChatGPT’s “memory” as allowing it to seem too lifelike by drawing on what you’ve said in previous conversations.

More on AI: AI Is Causing Cultural Stagnation, Researchers Find