As if the institution of political polling weren’t already fraught enough, pollsters are now surveying AI instead of real people to cut costs and save time.

As new research demonstrates, AI is clearly not up to the job — but that probably won’t stop any firms who’ve bought in to continue doing so.

In a white paper about the topic for the survey platform Verasight, data journalist G. Elliott Morris found, when comparing 1,500 “synthetic” survey respondents and 1,500 real people, that large language models (LLMs) were overall very bad at reflecting the views of actual human respondents.

Using six OpenAI models — GPT-4.1, GPT-4.1 nano, GPT-4.1 mini, GPT-4o, GPT-4o mini, and o4-mini — Morris instructed each LLM to respond as various demographics. In one example, the researcher prompted the LLMs to respond as a white 61-year-old woman in Florida who makes between $50,000 and $75,000 per year and who considers herself a moderate voter.

Using typical real-world political survey questions, the LLMs were asked things like “Do you approve or disapprove of the way Donald Trump is handling his job as president?” and given a five-point scale ranging from “strongly approve,” “slightly approve,” “slightly disapprove,” strongly disapprove” and “don’t know/not sure.”

The results weren’t exactly inspiring. The worst-performing model, which was not specified, was 23 points off from the real respondents overall, while the best-performing model, GPT-4o-mini, was 4 points off.

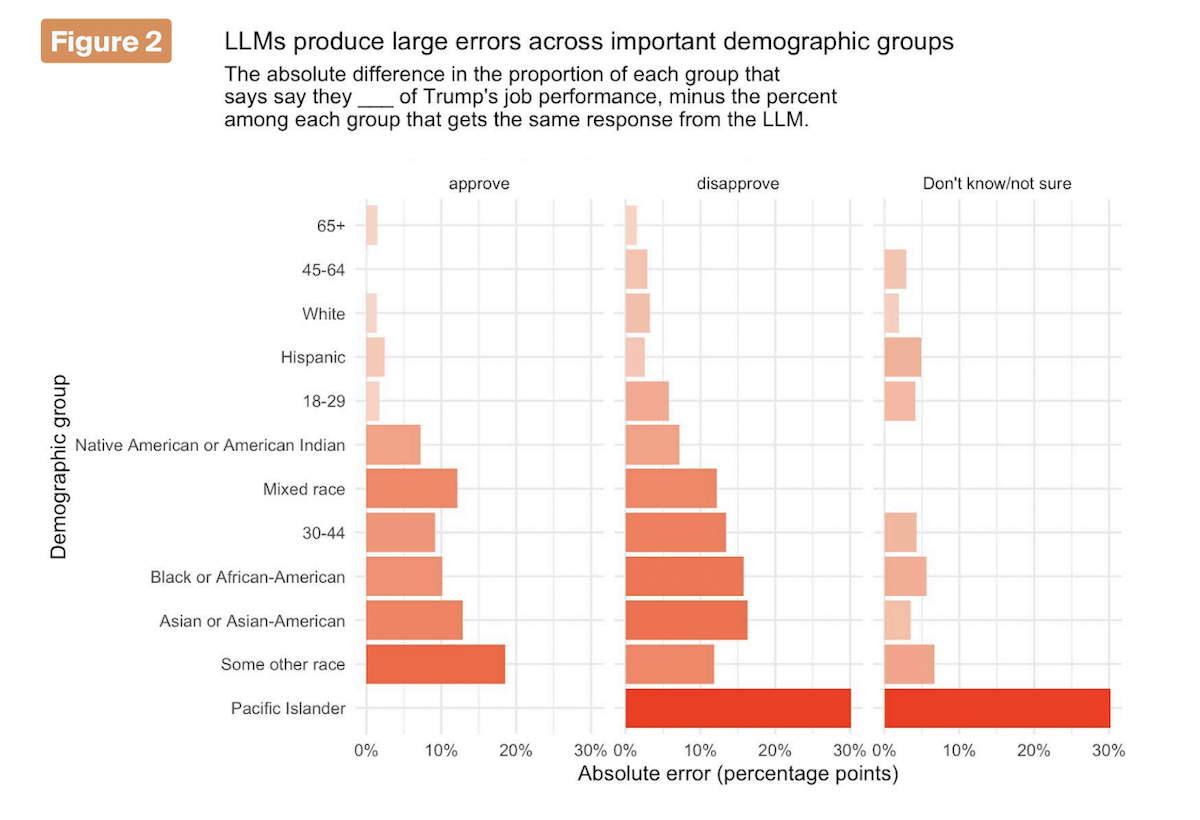

And the more closely Morris zoomed in, the worse things looked. As this graphic from the study shows, even the “voters” generated by the best-performing model, 4o-mini, veered further from reality as they were instructed to respond as groups who are less well represented in the United States population, like Black, Asian and Pacific Islander respondents.

For any pollster looking to do a good job, this is a big deal.

Imagine, for instance, a presidential campaign crafting its messaging for Black voters using the data above. When it comes to that cohort’s disapproval rating of Trump, there was a 15 percentage point difference between what actual people responded versus what 4o-mini predicted, with the AI significantly exaggerating that bloc’s disapproval rate for Trump.

Obviously, any campaign that used only that AI-generated data would miss the mark — instead of looking at the views of real respondents, it would be looking at a funhouse mirror reflection of a demographic cooked up by a language model with no access to actual data.

“The performance of our ‘synthetic sample’ is too poor to be useful for all of our research questions,” Morris wrote. “In computing overall population proportions, the technique above produces error rates at a minimum of several percentage points, too large to tolerate in academic, political, and most market-research contexts.”

“Synthetic samples generate such high errors at the subgroup level,” he continued, “that we do not trust them at all to represent key groups in the population.”

These results, while not entirely unexpected, fly in the face of the recent push to use AI-generated responses in political polling regardless of accuracy. One AI polling startup, Aaru, told Semafor after last November’s presidential election that even though it incorrectly predicted Kamala Harris would win, its methods were, somehow, still superior to traditional polling.

“A coin flip is a coin flip. 53-47 is not significantly different from 48-52,” Aaru cofounder Cameron Fink told the website. “Statistically speaking, we’re within the margin of error — so we did well.”

Heck, maybe that’s a good enough attitude to get hired by a political campaign — but it’s not going to do much help for any candidate trying to win.

More on AI and politics: AI Powering MAGA Botnet Confused by Trump’s Connections to Epstein, Starts Contradicting Itself