A wild game trapper just south of San Francisco was in for a colorful surprise when he began processing some feral hogs he had caught earlier this year.

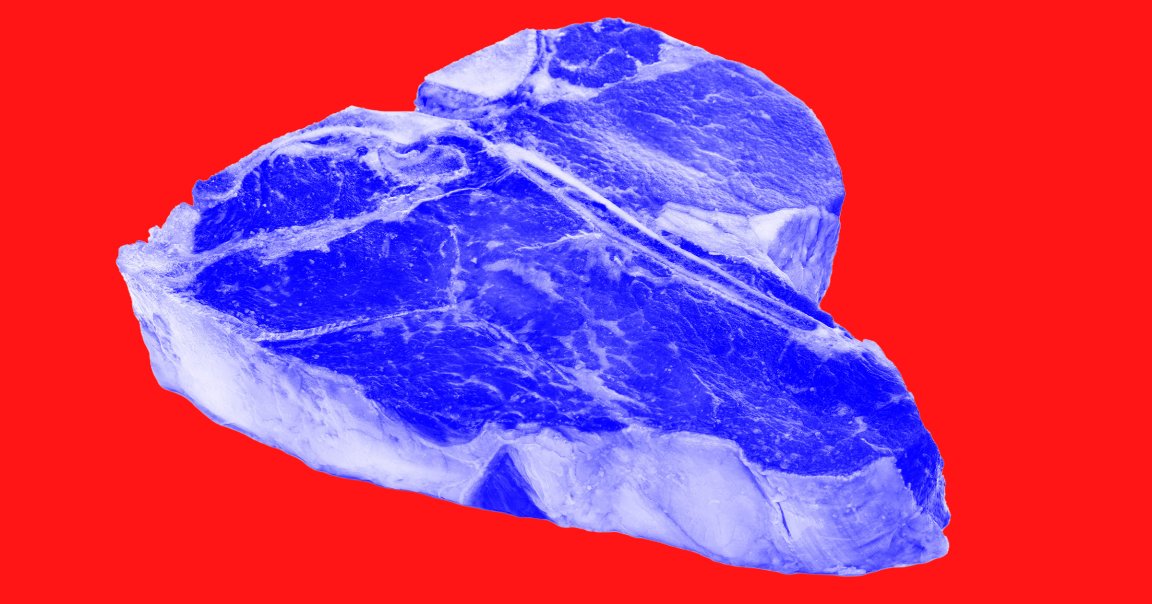

According to local news outlet SFGate, a number of the hogs — technically crossbreeds between domestic pigs and wild boars — appear to have had their muscles and fatty tissue stained blue after munching on a rat poison known as diphacinone.

The California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) confirmed this in a recent press release, after the department’s Wildlife Health Lab found traces of the deep blue pellets in one of the hog’s stomachs. The CDFW went on to note that rodent bait is typically dyed certain colors to identify it as poison.

Unfortunately, the hogs don’t seem to have gotten the memo. Local news station KSBW later reported that the proliferation of rat bait seems widespread across the county, as well as along a local river.

Bryan Flores, chief of Monterey county parks, said that the strange coloring is a “clear signal” to ward off hunters from contaminated game. “If you cut it open and the tissue is blue, you don’t eat blue meat,” he told KSBW.

The legality of poisonous bait for commercial and public use varies between various localities and countries. In California, for example, diphacinone is illegal for personal use, with one of the only exceptions being for commercial farm operations.

Though rodenticide poisoning in humans is rare, it does come with a high fatality rate relative to other poisons.

There’s also concern that it’s moving up the food chain through small rodents into larger predators. Due to the global use of diphacinone and rodenticides like it, the poisons are threatening critters like bobcats on Kiawah Island, caracals in South Africa, and monitor lizards in Asia.

A particularly astonishing case came when P-22, a widely beloved male mountain lion being tracked by researchers in Southern California, had to be euthanized due to complications arising from diphacinone exposure.

Wildlife foundations have been particularly vocal about seeking alternatives to rodenticides that threaten wildlife.

For individuals, this might mean staying on top of property management by clearing standing water, installing owl boxes, and using rat-resistant trash cans.

And when it comes to industrial operations, the best bet is probably integrated pest management (IPM), a sustainable approach that minimizes harm to adjacent wildlife.

The wild hogs — and those who hunt them — will thank you.

More on pollution: Woman Says Zuckerberg’s AI Data Center Filled Her Tap Water With Sediment