Moth Eyes

It seems there is no end to the uses of graphene—it can be made into a superconductor, improve fuel performance, and even seems to be the future of device fabrication. But now researchers from the University of Surrey in the UK just made a significant breakthrough with the wonder material—and it could finally make indoor solar cells possible.

The scientists behind the work started by studying the eyes of moths.

“We realized that the moth’s eye works in a particular way that traps electromagnetic waves very efficiently,” Professor Ravi Silva, head of the Advanced Technology Institute at the University of Surrey, tells Newsweek . “As a result of our studies, we’ve been able to mimic the surface of a moth’s eye and create an amazingly thin, efficient, light-absorbent material made of graphene.”

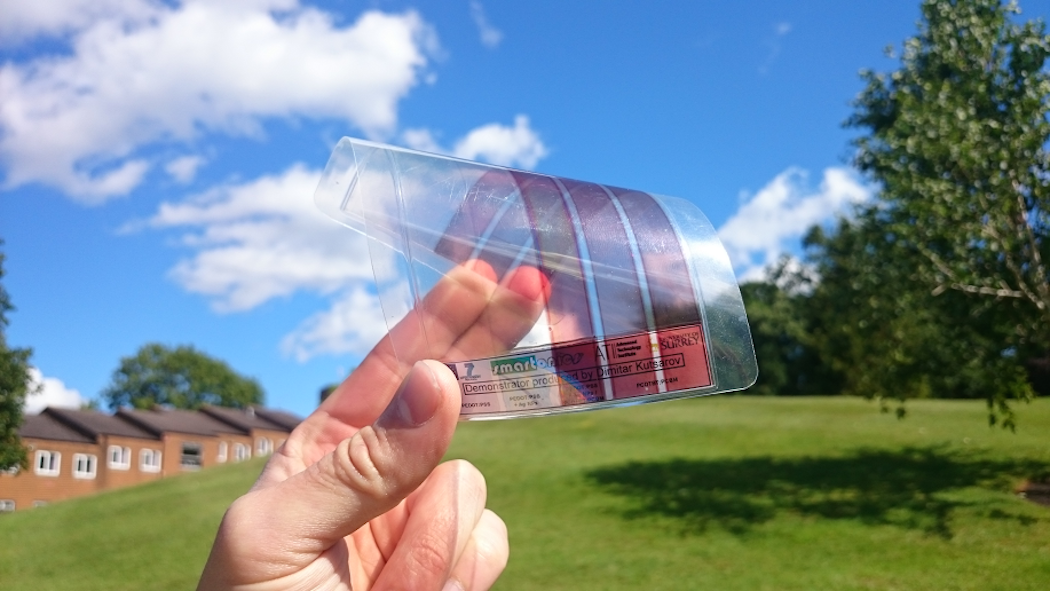

These graphene sheets, the scientists claim, are now the most light absorbent material ever created, which means it could be used to capture energy from indirect sunlight as well as ambient energy from smart devices such as clothes or wearable technology.

Graphene

Graphene is a material that has been lauded for its remarkable properties and numerous opportunities for application across different industries. It’s one-atom thick and made of carbon atoms in a honeycomb lattice. It is said to be 200 times stronger than steel, more conductive than copper, but still be as flexible as rubber.

“For many years people have been looking for graphene applications that will make it into mainstream use,” Silva says. “We are finally now getting to the point where these applications are going to happen. We think that with this work that is coming out, we can see an application very close because we’ve done something that was previously thought impossible: optimizing its incredible optical properties.”

This means using graphene technology to develop rectennas—rectifying antennas, which are capable of converting electromagnetic energy into direct current—can be used to power numerous small devices without needing batteries or wired connections.

The research was published recently in Science Advances.

Share This Article