The US National Academy of Medicine is looking to the US Food and Drugs Administration (FDA) to approve clinical trials to transfer DNA from healthy human eggs to diseased embryos.

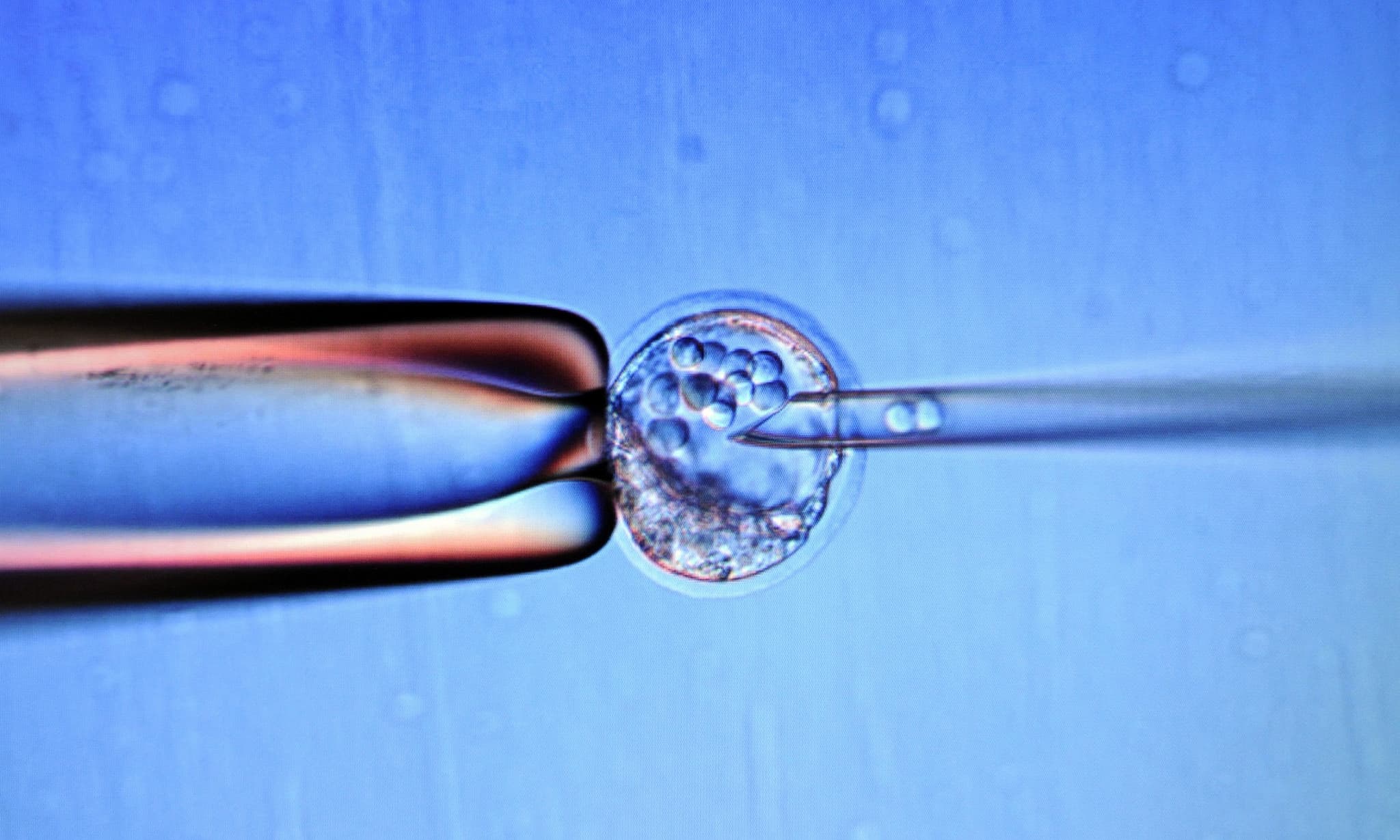

This controversial gene-therapy technique involves replacing an embryo's energy-producing mitochondria with a healthy mitochondria from a second woman. The goal here is to prevent diseases from being transmitted to future children.

However, the FDA is hesitant about this procedure due to the safety of mitochondrial replacement, and the psychological and social implications of children with three genetic parents.

Reports indicates that the academy panel suggests limiting the tests of mitochondrial replacement to male embryos as a safety precaution. Male offspring would not be able to pass their modified mitochondria to future generations, because a child inherits its mitochondria from its mother. It also outlines several additional steps to monitor the safety of mitochondrial replacement. These include following the children made by the technique for years and sharing the resulting data on their health.

The advisory panel says that, if mitochondrial replacement is proven safe in male offspring, it could be expanded to female embryos.

On the other side of the world, the United Kingdom approved mitochondrial replacement last year with no restrictions on the sex of the modified embryo. Some ethicist who advised the UK government on the implications of mitochondrial replacement argued that the risks of the technique are poorly understood, but others disagreed with the questions regarding the implications of the procedure, and it went through.

Other scientists comment on the decision

Shoukhrat Mitalopov is a reproductive-biology specialist at the Oregon Health Sciences University in Portland. In his opinion, the advisory panel's recommendation is a hollow victory. The FDA commissioned the US$1.1 million National Academy of Medicine review in 2014 after Mitalipov applied to perform a clinical trial of mitochondrial replacement therapy with human embryos.

But the fiscal year 2016 government spending bill enacted last month includes language preventing the FDA from approving any applications to implant modified human embryos into women.

The FDA says it cannot comment on any individual application, but confirms that the law covers mitochondrial transfer, even if the resulting genetic modifications cannot be passed to a third generation.

“The future seems very hazy compared to a few months ago,” Mitalipov says, given the restrictions included in the spending bill. Still, his lab is beginning to breed monkeys treated with mitochondrial replacement, in hopes of understanding how this genetic modification could affect subsequent generations of offspring.

However, the 2016 spending legislation also directs the FDA to appoint an independent committee — including experts from “faith-based institutions” — to review the National Academy of Medicine report and report back to Congress. The FDA says it is reviewing the report and cannot comment on its future plans.

Jeffrey Kahn, a bioethicist at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland, who led the academy panel, notes that it included a religious expert. As for the resulting report, he says, ”I feel like it's had a fairly rigorous review for all issues.”

Others disagree with the National Academy of Medicine panel’s conclusions. The new report “realised all the concerns and leapt to the conclusion that things should go forward despite all the concerns,” says Marcy Darnovsky, president of the non-profit Center for Genetics and Society in Berkeley, California, who has opposed mitochondrial replacement in humans on both safety and ethical grounds.

Darnovsky says that she would like to see an international agreement and legislation to ban techniques that edit embryos’ nuclear genomes. “I would have more faith in the argument if allowing this technology isn’t going to pave the way for more concerning forms of germline editing,” she says.

Yet, one must question why it is ethically responsible to edit the genes of non-human animals but irresponsible to conduct such tests on humans even if there are no associated safety concern. Hopefully, much of these murky waters will be waded in the coming years.

Share This Article