Instant Function

Electrodes implanted in the brain and spine have helped paralyzed monkeys walk. The neurologists behind the study reported that the implants restored function in the primates' legs almost instantaneously. The findings are detailed in Nature.

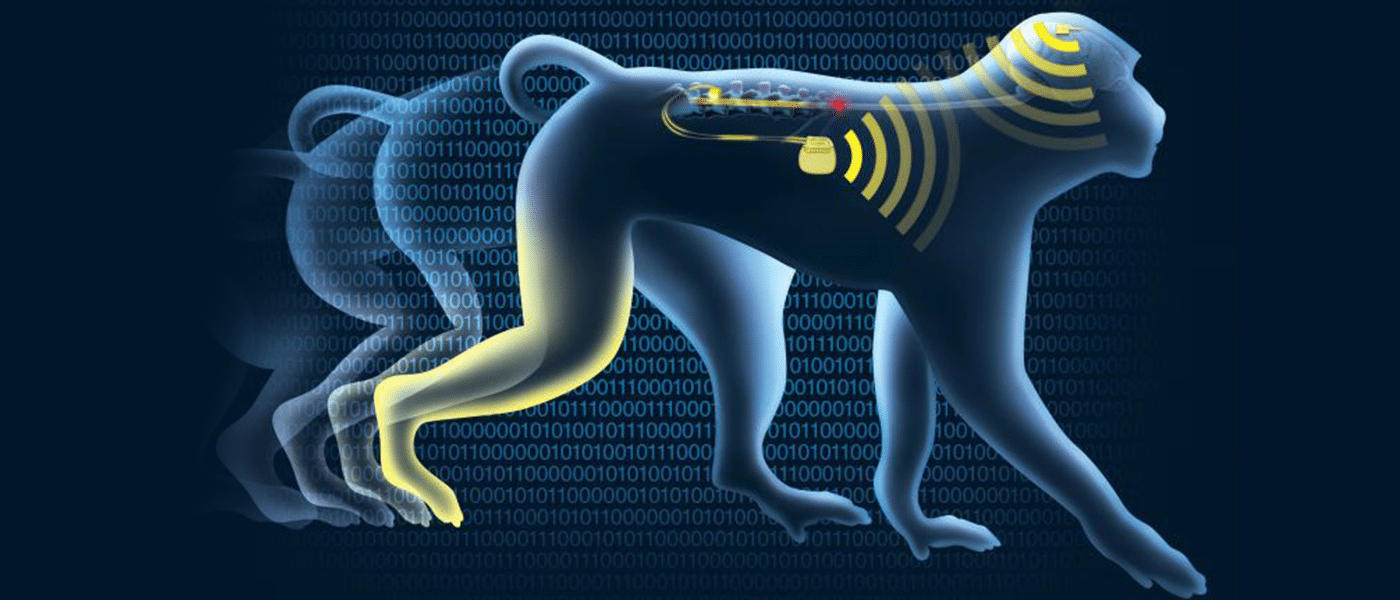

The spinal cord of the subject monkey was partially cut, so the legs had no way of communicating with the brain. To mend the brain-spine interface, electrodes were placed on key parts of the monkey's body. Implants were placed inside the monkey's brain at the part that controls leg movement, together with a wireless transmitter sitting outside the skull. Electrodes were also placed along the spinal cord, below the injury.

A computer program decoded brain signals indicative of leg movement and transmitted the signals to the electrodes in the spine. Within just a few seconds, the monkey was moving its leg. In a few days, it was walking on a treadmill.

"The primate was able to walk immediately once the brain-spine interface was activated. No physiotherapy or training was necessary," said Erwan Bezard, one of the authors of the study.

Primate-to-Primate

This study is a massive breakthrough—it's the first time implants have helped a primate walk. There has been much research to develop tech for paralyzed patients, but most lab trials were done on rodents. "It seems the principles learned in rats are now translating into primates," said Jen Collinger, a University of Pittsburgh bioengineer.

The results were astoundingly positive, but the researchers say that it will take at least a decade to fine-tune the technology for use in humans. Still, our bodies are greatly similar to that of monkeys, and the researchers believe transition could be quick.

Exciting news about the study is that the components that the researchers used are legal for human use in Switzerland. The Swiss group of the study have started clinical trial with eight people with partial leg paralysis.

We're all eager for further development in the study—an innovation that could greatly change the lives of approximately 282,000 people in the U.S. with spinal cord injuries.

Share This Article