No Need for Heat

Unlike those of typical electronics, circuits created by printing conductive polymers and "inks" onto surfaces like paper, fabric, glass, or foil are very thin and flexible. The properties of these printed electronics allow for a wider range of applications than traditional ones, everything from smart packaging to batteries for wearable devices.

The problem is, in order to achieve good conductivity, you need to apply enough heat to the nanoparticles in these inks to make them melt together. Unfortunately, that means these circuits can't be printed on low-cost materials that aren't as heat-resistant. You need something more durable and, therefore, something more expensive.

The cost of printed electronics is a long-standing barrier to wider usage that researchers from Duke University say they may now be able to address. According to their research, all that's needed is a simple tweak in the process — change the shape of the nanoparticles in the ink, and you can eliminate the need for heat.

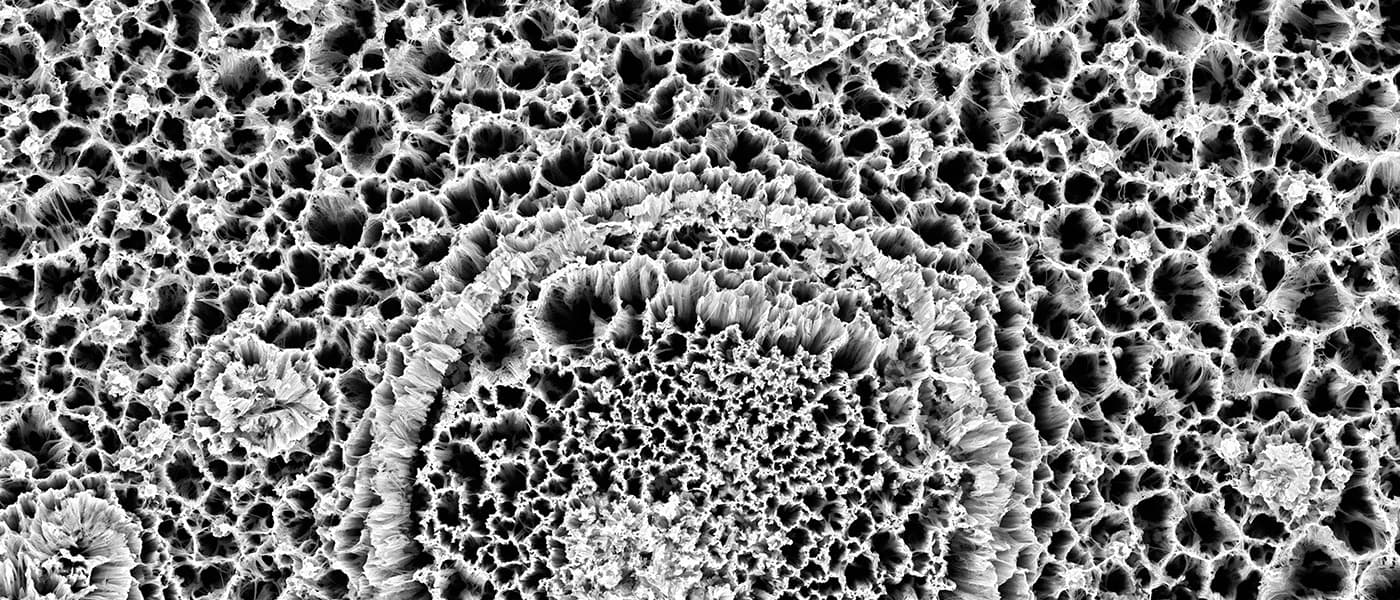

As part of their study, the researchers created multiple films using a variety of silver nanostructures: short and long nanowires, nanospheres, and microflakes. First, they mixed the nanostructures with distilled water to create inks. They then used glass slides, double-sided tape, and heat applied in a range of temperatures to create films out of these inks. Tests on the different films them showed that electrons flowed easier through films made of silver nanowires than those made of nanospheres or microflakes.

While knowing that nanowires are the most conductive shape was valuable (if unsurprising) information to the researchers, most important was finding out the extent of their conductivity. "The nanowires had a 4,000 times higher conductivity than the more commonly used silver nanoparticles that you would find in printed antennas for RFID tags," said Benjamin Wiley, assistant professor of chemistry at Duke.

In fact, the electrons flowed with such ease through the nanowire films that they could be functional without the particles being melted together. "If you use nanowires, then you don't have to heat the printed circuits up to such high temperature and you can use cheaper plastics or paper," said Wiley.

A Range of Applications

With heat no longer a factor limiting production, these circuits could be printed on cheaper materials, thus opening up the technology to additional applications. According to the researchers, these applications could include solar cells, touch-screens, batteries, LEDS, and even bio-electric devices.

The cost of the material on which these circuits could be printed hasn't been the only obstacle to their wider usage — the cost of the silver is also a factor. Next, the researchers want to study what materials they could eliminate from the devices to figure out the exact amount of silver needed to achieve optimum conductivity.

They’re currently studying whether silver-coated copper nanowires, a cheaper alternative to pure silver nanowires, will deliver the same effect as a part of that effort, and they're also experimenting with aerosol jets as a method of printing silver nanowire inks in usable circuits.

Share This Article