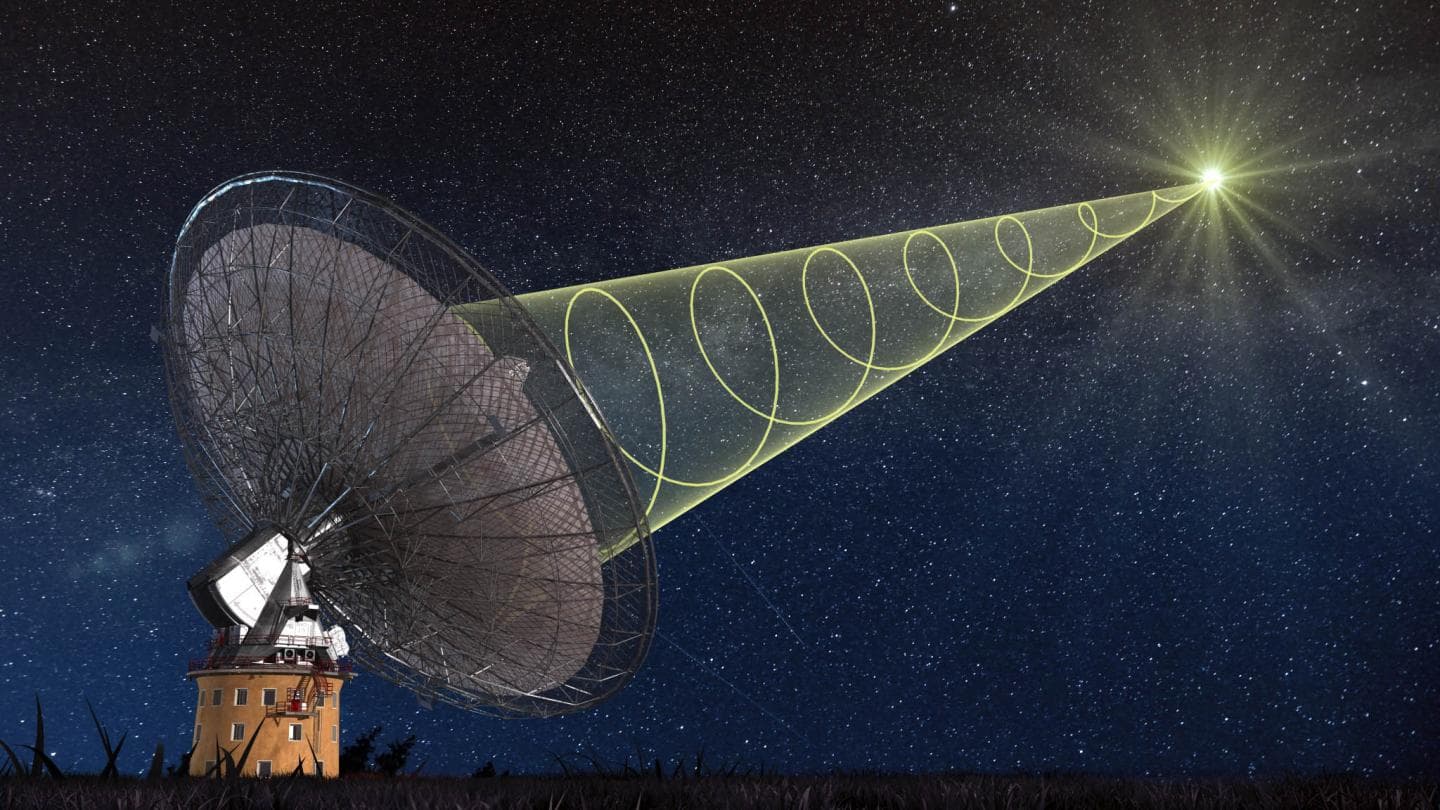

In a study published in a recent edition of the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, researchers have detected something called a fast radio burst (FRB): an unusual phenomenon that first surfaced in 2007, whereby a sharp, but brief, burst of radio waves is picked up by Earth-based radio telescopes.

When the first one happened, it was only learned of after-the-fact, when astronomers were looking through data collected by eastern Australia's 'Parkes Radio Telescope.' In the years that followed, Parkes detected six nearly identical bursts, while another was found in Arecibo Telescope's archival data.

Given their brevity (mere milliseconds after they appear, they are gone) and how it's almost impossible to predict where one will happen, astronomers have had a difficult time pinpointing their location, that is, until recently.

The Mechanism of a FRB:

In order to see an RFB in real-time, a team of Australian researchers — led by Emily Petroff from Swinburne University of Technology in Australia — have devised a clever technique to pick up a fast radio burst as it happens (though, to be pedantic, nothing happens in real time. These burst actually happened hundreds of millions, maybe billions, of years ago. They just didn't make it to Earth until now).

In their paper, they note that they believe the source of emission lurks around 5.5 billion light-years away: a notion that appears to be supported by other observatories that conducted follow-up observations in the minutes that followed. These observatories include NASA's Swift — a multiwavelength observatory that specializes in gamma-ray bursts — and the Nordic Optical Telescope.

According to one researcher, Daniele Malesani from the Dark Cosmology Center in Denmark, the former yielded not one, but two x-ray sources in the field of view the FRB is believed to come from. With the latter observatory, "We observed in visible light and we could see that there were two quasars, that is to say, active black holes. They had nothing to do with the radio wave bursts, but just happen to be located in the same direction."

Whittling The Options Down:

"We found out what it wasn't. The burst could have hurled out as much energy in a few milliseconds as the Sun does in an entire day. But the fact that we did not see light in other wavelengths eliminates a number of astronomical phenomena that are associated with violent events such as gamma-ray bursts from exploding stars and supernovae, which were otherwise candidates for the burst," notes Malesani.

Either way, the team did not come up empty-handed. Apparently, Parkes caught a glimpse of strange polarization in its light. Polarization, simply put, "is the direction in which electromagnetic waves oscillate and they can be linearly or circularly polarised. The signal from the radio wave burst was more than 20 percent circularly polarised and it suggests that there is a magnetic field in the vicinity."

"The theories are now that the radio wave burst might be linked to a very compact type of object — such as neutron stars or black holes and the bursts could be connected to collisions or 'star quakes.' Now we know more about what we should be looking for," says Daniele Malesani.

Share This Article