Transplant lungs can only survive for a short period of time outside the human body. In fact, only around a quarter meet criteria for transplantation, according to the American Lung Association.

That's why a team of researchers at Columbia University in New York have decided to find an alternative, extending the shelf life of human lungs intended to be transplanted — by hooking them up to live pigs, as detailed in a new paper published in Nature Medicine today.

The procedure could allow deteriorated or damaged lungs destined for transplantation to recover within just 24 hours, New Scientist reports.

The research could even one day allow human patients to act as their own surrogates, healing transplant lungs destined for their own bodies via a catheter in their neck, according to The New York Times.

Currently, health practitioners attempt to recover deteriorated lungs using complicated machinery called EVLP (ex vivo lung perfusion) that pumps air and fluids through the lungs — but only with limited success.

To improve on this idea, a team of researchers from Columbia University in New York wondered if hooking up damaged lungs to living pigs could help remove toxins and add nutrients.

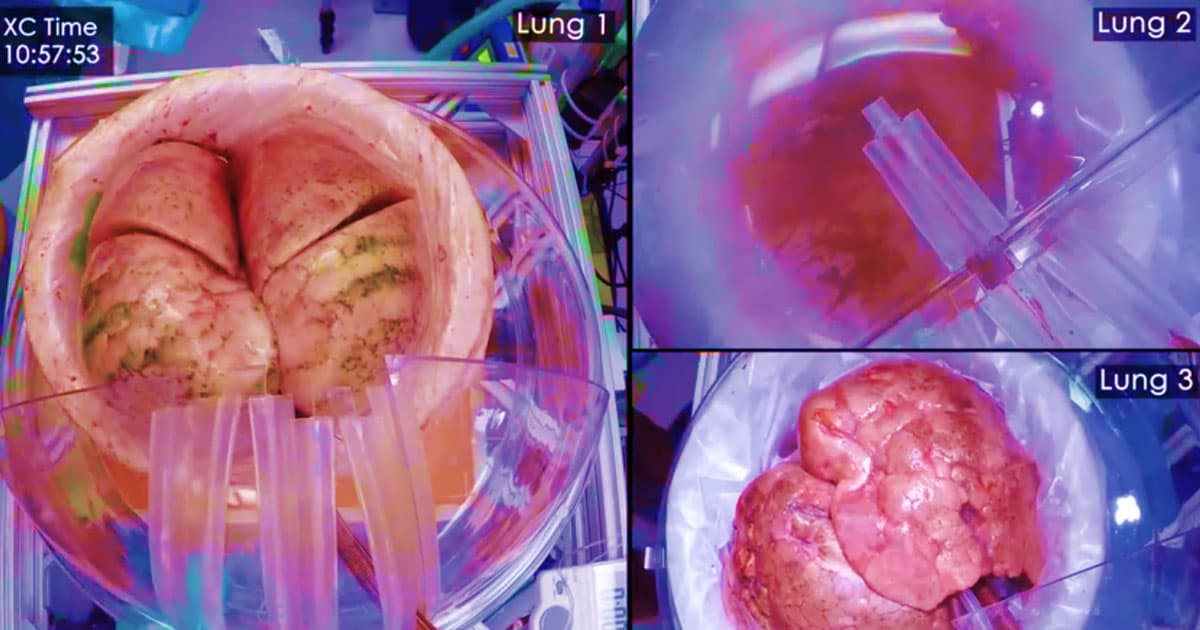

In an experiment, the team connected half a dozen human lungs from brain dead patients to the circulatory systems of anesthetized pigs for 24 hour periods.

By pumping air into the lungs inside plastic boxes and adding immunosuppressant drugs that ensured the immune systems wouldn't reject the alien lung, the team found that the lungs' capacity to deliver oxygen improved considerably. Even a lung that spent 48 hours outside the body had recovered.

The technique could revolutionize the medicine of transplants.

"If there were a way to maintain organs in a healthy state outside the body for a day or several days, then many things would change in transplantation," Robert Bartlett, a surgeon who developed a machine similar to the EVLP, who was not involved in the study, told STAT News. "You could have perfect matching. You could treat organs injured outside the body until they’re working well."

"That’s remarkable," James Fildes, regenerative medicine lecturer at the University of Manchester, UK, who wasn’t involved in the research, told New Scientist. "My expectation would be that that lung would be destroyed, but actually it doesn’t look like it is at all."

Before implanting the resulting lungs into humans, the team wants to repeat the experiment with more lungs, as the procedure comes with plenty of risks. White cells that made it from the pig into the lungs could trigger a dangerous immune reactions in human recipients, for instance.

Some lungs may be beyond repair despite the surrogate pigs, co-author Gordana Vunjak-Novakovic admitted to New Scientist, but "if you can salvage two out of every four that are rejected, you can increase the number of lungs available to patients by three times."

"If we could expand the donor pool, we could avoid a lot of waiting-list deaths and could be more open-minded about who could have a transplant," Matthew Bacchetta, lung transplant surgeon at Vanderbilt University and lead author of the study, told NYT.

The team is hoping the technique could "serve as a complementary approach to clinical EVLP to recover injured donor lungs that could not otherwise be utilized for transplantation," as they note in their paper.

Luckily, no pig was hurt during the experiments. According to the researchers, the pigs were left with no long-lasting effects. Some were even able to play around with toys while hooked up during a previous experiment.

"It’s a transformative idea that would allow a jump forward in the field," Zachary Kon, surgical director of the lung transplant center at New York University Langone Medical Center, told the Times.

Share This Article

READ MORE: Damaged human lungs revived for transplant by connecting them to a pig [New Scientist]

More on lung transplants: Japanese Scientist Wants to Grow Human Organs In Animal Embryos