Growing Back

It is common knowledge that science is currently at work growing organs, limbs, eye parts, and other parts of the body that could possibly be damaged and need replacement. But what of the possibility that we don't need to replace lost parts? Will there be a time when they will just grow back?

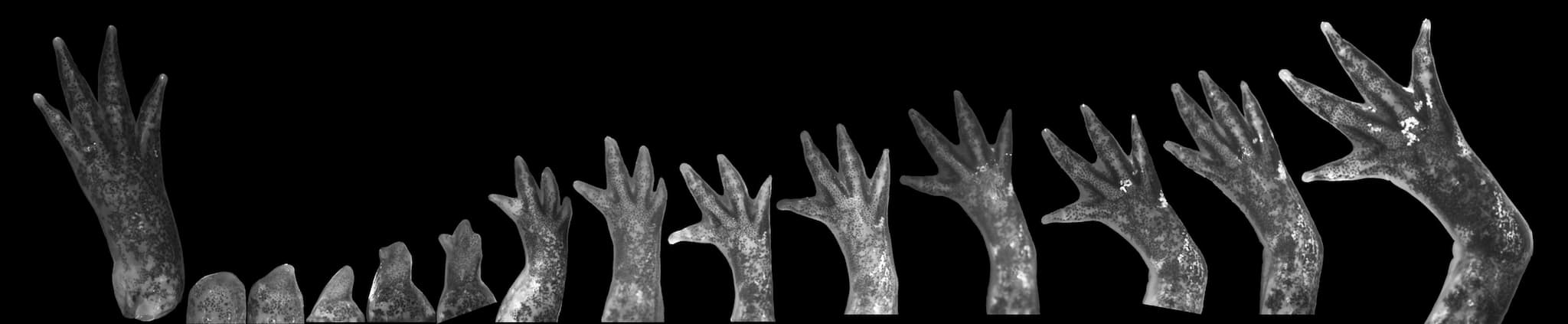

A particular field of biology studies animals that are actually capable of this: regeneration biology. Studying salamanders, lizards, and flatworms, these scientists look at the mechanisms these animals use to regenerate lost body parts, in the hope that one day humans could too.

The process these animals use are actually well-documented. When there is a wound, the outermost layer of skin covers up this wound. A bump then appears, called the wound epidermis. It sends instructions to cells near and beneath it and mature cells become immature ones called blastema. And then Nerve cells start to regenerate.

The blastema is key to regeneration. Those immature cells start dividing and differentiating into the cells of the lost limb. There is also some form of memory that tells the process when to stop, with the blastema only regenerating the lost hand or leg, no more.

Road Bumps

While this mechanism is known, several obstacles are still in the way. Salamanders, lizards, and worms aren't exactly the best lab animals, not very comfortable in a lab environment.

Also, studying salamander genes is harder, since their genomes are much more complex. They carry ten times the amount of DNA as ours, making gene sequencing tricky. It was only until recently that scientists figured out how to edit and remove genes from their gene sequences.

Also, this process can be slow. A 4 mm (.16 inches) limb can take as much as 400 days to grow back. What of something as large as an adult arm? Years? Decades?

Funding tends to funnel to advancements which see much faster results, like stem cells. However, one researcher envisions a more symbiotic relationship between the disciplines Enrique Amaya, developmental biologist at the University of Manchester, said “I’d argue that stem cell researchers need the kind of work that we do. We’re still damn ignorant about how cells behave, and how to control their behavior.”

Share This Article