According to China's National Central Cancer Registry, Esophageal cancer is one of the most common forms of cancer in China. Like many other types, cancer of the esophagus can be treated with chemotherapy. But, as is also true of other forms of cancer, chemotherapy isn't always successful. In China, and around the world, there's a great need for the development of new treatments.

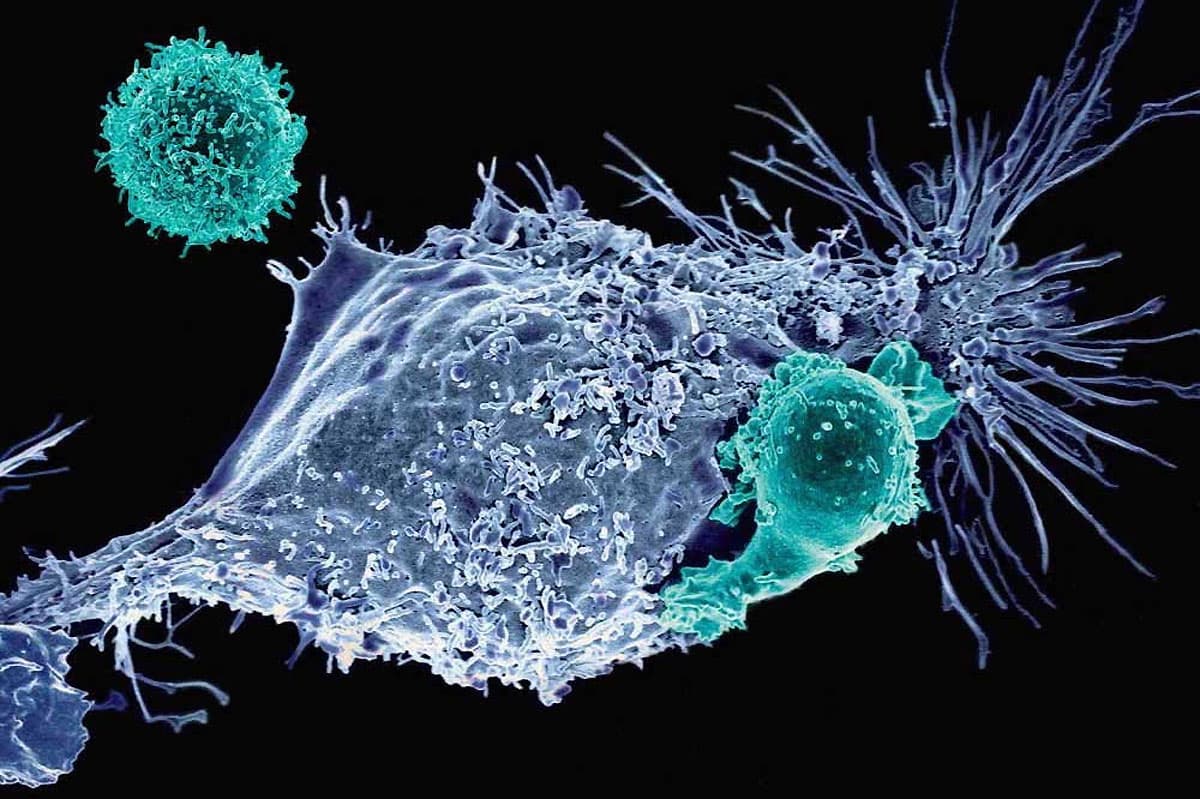

Dr. Shixiu Wu, president of the Hangzhou Cancer Hospital, has tested a somewhat new treatment that takes a patient's T-cells from the body, genetically edits them to target cancerous cells, then puts the altered cells back. If the process sounds at all familiar, it's probably because using T-cells in this manner was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration back in August 2017.

We reported on a pair of CAR-T studies in December that used T-cells to fight cancer, as will the first CRISPR trial set to take place in the United States.

The other research involving modified T-cells to fight cancer doesn't diminish the impact of Wu's work, though. In fact, Wu believes the study is one of the most advanced involving CRISPR in China. Currently, Wu's T-cell treatment is being tested on 21 people with advanced Esophageal cancer that didn't respond to other treatments. So far, 40 percent of his patients have responded positively to the new treatment.

"If they have not received this treatment they will die — most of them will die in three to six months," Wu told NPR.

There are those, like Lainie Ross a bioethicist at the University of Chicago, who are worried about the experiments in China; primarily because the country's medical research isn't as regulated as it is elsewhere. Ross told NPR there is concern that Chinese doctors and researchers could be rushing the experiment along, putting their patients at risk.

"My concern is: Are we really ready? There so much about CRISPR that we don't understand," Ross explained to NPR. "We could be doing more harm than benefit. We need to very, very cautious. This an incredibly powerful tool."

In response to concerns expressed about the research, Wu has made clear that patients are told about the risks of the treatment beforehand — and many of them consent to receive it despite them. "Chinese patients want to be cured very much," Wu said. "There's a Chinese saying: A living dog is better than a dead lion. So patients are willing to try new cures. That's why the ethics committee and the lab are very positive about this."

Wu has since started treating patients with other forms of cancer as well, specifically pancreatic cancer. "We [are] just beginning. We should improve it to get more benefits for the patients," he said. "If you don't try it, you'll never know."

Share This Article